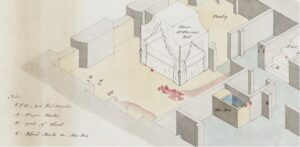

On July 4th 1862, 33-year-old servant Jess McPherson was discovered dead at her master’s home at 17 Sandyford Place, Glasgow, the victim of forty blows to her head, face and body, which had been administered with an iron cleaver. There was blood all over the bedroom, lobby and kitchen, and some of the victims’s clothing and belongings (as well as silverware from the house) were missing. But strangely, the kitchen and bedroom floors had recently been washed, as had the face, chest and neck of the corpse, yet bloody footprints were still visible.

The first suspect was ‘Old’ [James] Fleming, the father of the owner of the house. Fleming was staying alone in the house at the time of the murder, and claimed he had not realised McPherson was laying in her bedroom murdered (the bedroom door was locked). In the past Fleming had gotten a servant girl pregnant, and the police conjectured that he may have murdered McPherson after she refused his amorous advances. But the case evolved when a pawnbroker, who read about the story in the newspaper, reported receiving the missing silverware from a woman called Mary McDonald. This was a name sometimes used by Jessie McLachlan, a former servant at 17 Sandyford Place and best friend of the victim.

McLachlan, a heretofore unoffending young woman, was promptly arrested by the police and put on trial. Blood-stained clothes were found at her house. The chief witness against her was James Fleming, in whom the authorities suddenly displayed a new-found trust and respect. It was proved that Jessie MacLachlan had been present at the house too, although she lied about this (and other things) at her trial. The Sandyford murder was the first Scottish police case in which forensic photography was used to help solve the crime; McLachlan was asked to place her foot in a bucket of cows blood and then step on a plank of wood. This bloody footprint was then matched to a photograph from the murder scene.

At the conclusion of the court proceedings, the presiding judge, Lord Deas, inveighed against the defendent for no fewer than four hours. As a contemporary law journal put it, he “put his foot fiercely into one scale [of justice] and kicked at the other”. After this damning summing-up, the jury retired for just fifteen minutes before delivering a guilty verdict. But in a twist worthy of Agatha Christie, Jessie McLachlan then had her counsel read a remarkable statement on her behalf, in which she implicated James Fleming, as the murderer. Dismissing the defendant’s story as “wicked falsehoods”, Lord Deas sentenced the unfortunate young woman to death by hanging.

Fortunately for McLachlan, public outcry, most of whom believed James Fleming to be the real murderer, led to a stay of execution and life imprisonment. She was eventually released from prison in 1877 and emigrated to America to be reunited with her son (who had only been 3 years old at the time of the murder).

By the 1930s, the Sandyford Murder was so well known that it got a passing mention in Dorothy L Sayer’s Busman’s Honeymoon, Gladys Mitchell’s When Last I Died, and John Dickson Carr’s Seeing is Believing. Dorothy Erskine Muir used it as the basis for her first detective novel In Muffled Night (1933), changing the setting and the timing, and imagining a very different set of circumstances surrounding the main players.

Sources and further reading:

Hansards: The Glasgow Murder-Case of Jessie MacLachlan

The Ancient Art of Advocacy: The Sandyford Murder

inews.co.uk: The chilling curse of Glasgow’s ‘Square Mile of Murder’

Excerpt from Chrtianna Brands’ Heaven Knows Who

Podcast: Square Mile of Murder