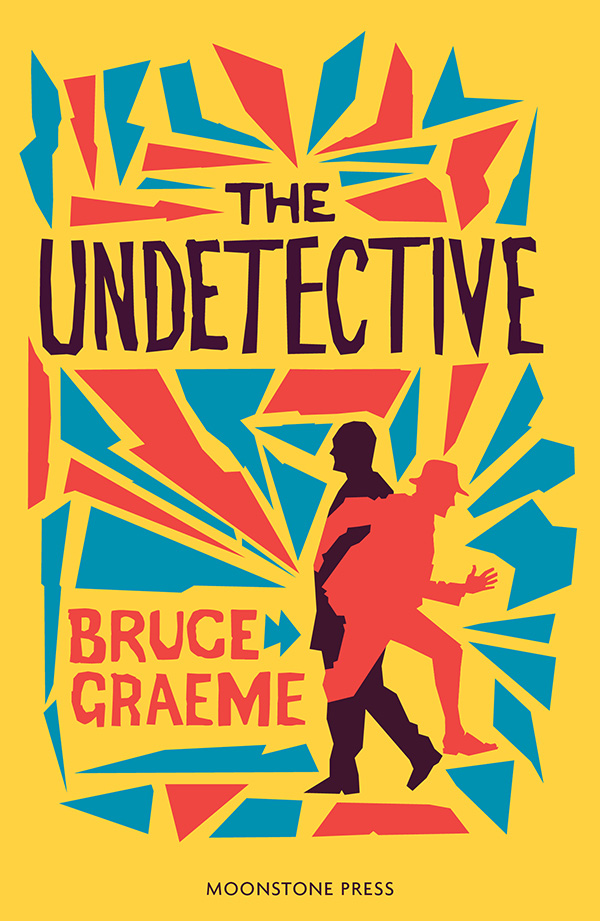

The Undetective (1962)

“It was my own fault, of course. I realized that when it was too late.”

Crime writer Iain Carter has recently married and is struggling to make a decent living as an author. His brother-in-law is a likable but slightly indiscreet constable, and Iain decides to use this inside knowledge to write a satirical series featuring a pompous dictatorial police superintendent. To protect his identity, Iain creates an elaborately designed pseudonym, John Ky Lowell, that can’t be traced back to him. When the first book by Lowell, The Undetective, proves to be a huge success, Iain finds he must take increasingly convoluted steps to protect his secret from the press, the police and the taxman. But the real trouble begins when a local bookmaker is killed, and Iain finds his mysterious alter-ego is the prime suspect.

Date of release: November 2020

£9.99

By Bruce Graeme (pseudonym of Graham Montague Jeffries)

First published in 1962 by Hutchinson & Co Ltd

Paperback

206pp

ISBN 9781899000241

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

It was my own fault, of course. I realized that when it was too late.

But this I say with absolute sincerity: if I could have foreseen the consequences I should have hesitated a long time before making fools of the police, before exasperating them to the point when they welcomed an opportunity which was not only in the line of duty, but, simultaneously, gave them what they hoped would be a chance of getting their own back on me.

Here is my biography, previous to my meeting Susan for the first time.

“CARTER, Iain Wallace, Author and Barrister-at-Law, eldest son of Robert Iain Carter, solicitor, of Two Cedars, Cornwall Road, and Jane Margaret Wallace. Age: 25 years, four months. Educated: West London Preparatory School: Arundel. Details of career: Admitted Gray’s Inn, published Barrister-at-Law, served one year’s pupillage in Chambers of Gordon Macintosh, with signal lack of success, retired gracefully from the Law to take up Literature. Cajoled, pestered, and practically blackmailed publisher-uncle, James Dougall of Dougall and Smith, to publish first novel. Miraculously, it nearly did not lose money, on the strength of which Dougall and Smith published the next five books.”

I’ll say this for my parents, my father in particular. They were sports. In spite of their bitter disappointment that I was hopeless as a lawyer, they did not rail at me as they might have done. As Father said: ‘To have as near relative a solicitor, who could pass on as many briefs as he could handle, is a gift of God for which a newly called barrister would normally give five years of his life; but it’s your life, Iain, and I do not intend to try and influence you in the way you lead it.’

‘You wouldn’t have briefed me for long. You’d have lost all your clients.’

He sighed. ‘I must admit that you were peculiarly inept. Perhaps you have made a wise decision. What do you propose to do instead?’

‘Write.’

‘Write!’ He looked startled.

‘Books. Detective stories.’

‘Good gracious! But what do you know about writing books?’

‘Nothing, so far. But don’t forget writing is in the family. There’s Cousin Philip, Uncle William, and great-great-Grandfather Septimus. To say nothing of Uncle James, who is a publisher.’

‘True, true. Though I have not heard that any of them made a fortune from their books,’ he drily added.

‘I know, that’s why I shall have to take a job.’

‘What as?’

‘I haven’t thought that much ahead, but as long as it brings me in enough to live for a few years, until I get established…’

‘You do not have to take a position, Iain. I am not a wealthy man by some standards, but neither am I poor. I will give you an allowance

of six hundred a year for some years—’

‘No, Father, I won’t take it…’

But ultimately I did, and ultimately I wrote my first novel, which Uncle James offered to publish on normal first-novel terms. £100 advance on account of royalties of 10 per cent to 2,500 copies, 12½ per cent from 2,500 to 5,000 copies, and 15 per cent thereafter.

‘Accepted,’ I promptly agreed.

He appeared not to hear me but continued: ‘Dougall and Smith to handle all subsidiary rights—’

‘What!’

‘Fifty per cent to you for paper-back rights, eighty-five per cent on sales to the U.S.A. and foreign translations, eighty-five per cent—’

‘No.’

He paused, looked up. ‘No what?’

‘I’m not giving you any cut in subsidiary rights.’

‘In that case—’

‘I have been told of at least six publishing firms who do not ask for subsidiary rights.’

‘In that case, naturally, you will offer your book to them.’

‘But you are my uncle,’ I protested. ‘Let’s keep it in the family.’

‘I am also a business man, not a philanthropist. In these days of high production costs a publisher considers himself lucky not to lose money publishing fiction. It is only by having a share in the sale of

subsidiary rights that he can hope to make profits.’

‘If you are not a philanthropist why are you offering to publish my book?’

As a Scot, Uncle James isn’t so easily defeated in argument. ‘Merely because you are my nephew,’ he blandly replied. ‘It is your

idea to keep it in the family.’

So One Case for O’Shea was published. Thanks to its being adapted as a radio play for B.B.C.’s Saturday Night Theatre, it nearly did not lose money, as recorded in my biography. As ninety-nine out of every

hundred detective stories aren’t heard in Saturday Night Theatre, or on any other night in the week, it is amazing how publishers continue to operate. Perhaps Mr. Parkinson will consider the problem and one

day propound another of his famous Laws.

Father and Mother were very pleased with One Case for O’Shea. ‘Could be worse,’ Father admitted after he had read it. ‘Blood tells,’ he added. I knew he was thinking of great-great-Grandfather Septimus. ‘Pity your knowledge of the law isn’t as sound as your writing,’ headded in that dry way of his. ‘But, then, you are only a barrister.’

Even Anne was so proud of being connected with me that for at least one week she carried the book about with her wherever she went—Anne’s my kid sister, four years younger than I.

So much for those earlier years. On the eve of publication of my sixth book, Shadow Crime, Father gave a party for the two of us: it chanced to be his fifty-second birthday. That night the house was burgled. Whether it was a case of cause and effect I cannot say. Perhaps the line of parked cars outside the house attracted the attention of a passing burglar.

The following morning a detective from our division called on Father. ‘Detective-Constable Meredith,’ he introduced himself in a crisp voice.

The two men shook hands. ‘My son, Iain.’

‘Mr. Iain Carter! The writer of detective stories?’

‘Fame at last! What do you think of that, Father? I’m beginning to be known by name.’

Meredith grinned. ‘I’m a prolific reader of detective stories, sir. There are not many published I don’t read.’

I wasn’t going to be robbed of my first sweet moment of success. ‘You recognized my name, that’s something.’

‘It’s part of our training to remember names and faces. But I like your books better than most, if you don’t mind me saying so.’

‘Mind! I’m overjoyed.’

Father coughed.

Meredith looked embarrassed. ‘I’m sorry, sir.’

Father chuckled. ‘You don’t have to be, but I have an appointment at the office in…’ He glanced at his watch. ‘Half an hour’s time.’

‘I won’t keep you long, sir, just long enough for a list of the stolen property…’

Father gave this, and left for his appointment. Meredith questioned me for a time, but there was not much I could tell him. In any case, I had a feeling that he had already guessed the

identity of the burglar. When I bluntly put this question to him he laughed.

‘I should have remembered that you have some knowledge of crime and police investigation. Your guess is a good one. Everything about this job bears the hallmark of an old friend of mine who’s been

inside seven or eight times.’

‘They don’t learn, do they? Might as well leave a visiting card, some of them. What will you do? Ask him to prove an alibi?’

‘Yes, and quickly, before he has time to cook one up. I may be lucky and find him still in bed.’

Meredith not only found the man in bed, but some of the stolen goods still underneath it. I met him again at the subsequent magistrates’court proceedings. After the thief had wisely pleaded ‘Guilty’, and the case had been sent for sentence at the next Assizes, I asked the constable whether he would care to have a drink with me at the George and Dragon.

He looked at his watch, and nodded. ‘I think I can spare a few minutes, sir, thanks to Tom pleading guilty.’

We chattered awhile over our beers. I found myself beginning to like the man. I judged him to be not much older than I. With plenty of blue-black hair, brown eyes, quick speech, uninhibited laughter, and a slightly exotic cast of features he gave me the impression of being partly European. Italian, perhaps. His figure was slight, athletic. I wasn’t surprised to hear him mention squash-racquets.

‘Do you play much?’ I asked him.

‘As often as I can.’ He grinned. ‘Not as often as I would like to.’

‘Are you good?’

‘So-so, not match-winning standard.’

‘Care to give me a game some time? I need some hard exercise.’

‘Love to,’ he promptly answered. Then he looked at me with those bright, speculative eyes of his. ‘How good are you?’

‘So-so, not match-winning standard.’

‘Fair enough.’ He laughed, and the genuine carefree note in it made me think that he was glad to have an opportunity of laughing with someone unconnected with his work.

Later that week we played squash, and each found that the other had told the truth about his play. We were both reasonably good; a fair match for the other. We had a thoroughly energetic and enjoyable half-hour’s play, and had no difficulty at all in subsequently downing a pint of bitter apiece.

That was the first of several meetings at the squash-courts; irregular, by nature of Meredith’s work. A detective’s time is never his own, I learned. For instance, one night, as he was leaving his office to keep an appointment with me, the Super met him face to face.

‘Where are you off to?’ the Super grimly asked. ‘Squash again?’ He didn’t have to be a detective to deduce this from the sports-bag which Meredith was carrying.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘That’s what you think. There’s a juicy one just reported from three, Thurlow Road. There’s only you and me available.’

‘Have I time to ’phone, sir?’

‘No. Tell the desk-sergeant. He will give the good news to your friend.’

So that night I was deprived of a game. It was no particular consolation for me to read, the next morning, gory reports of the ‘juicy one’ which had been responsible: a couple of women brutally murdered by a sex-maniac.

It so happened that this particular crime was to have indirect consequences for me. The next time Meredith turned up for a game of squash he was accompanied by a girl.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.