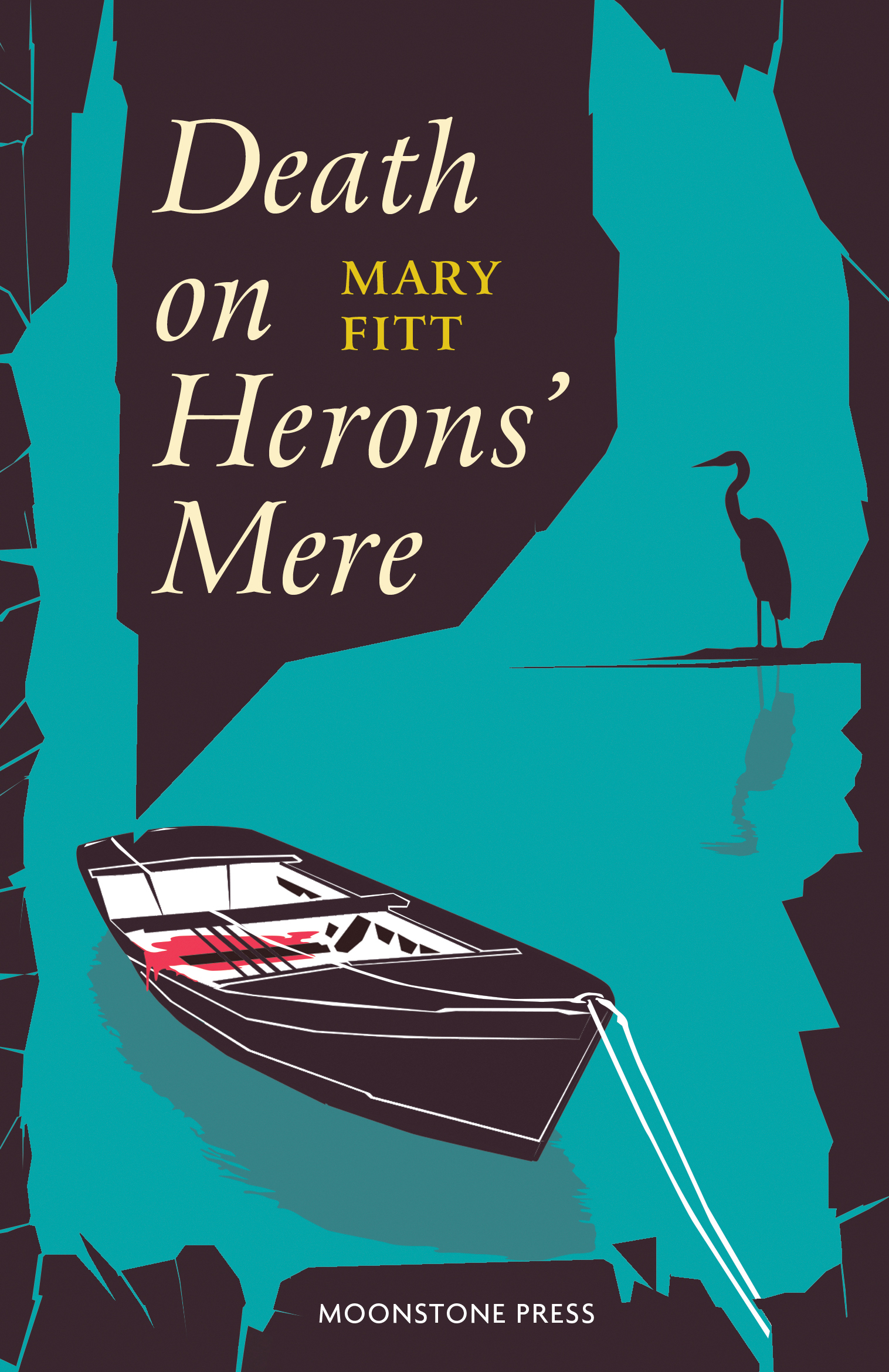

Death on Herons Mere

‘Mr Gabb, your son did not commit suicide. He was murdered.’

Simon Gabb has everything – or so it seems: a beautiful house on a large estate, a flourishing business and two sons, both evidently endowed with the capacity to carry on the family firm. One is brilliant and inventive, the other dependable and efficient. And yet something is manifestly wrong. A secret invention, on which his business is engaged for the government, becomes known to those who have no right to such information. But how and where did the leak occur? It is a conundrum which creates suspicion and dissension within the family and engulfs everyone who dines with them one Saturday night. The next morning, Gabb’s elder son, Giles, who, despite his oddities of behaviour, has shown such promise, is found dead by the lake. Smouldering emotions at once flare up, further deepening the mystery that Inspector Mallett must unravel.

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1941 by Michael Joseph Ltd

Paperback

254pp

ISBN 9781899000463

eISBN 9781899000470

Available May 2, 2022

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

It was the half-hour before dinner. In the immense drawing-room of Herons’ Hall, Simon Gabb’s guests waited without impatience for the summons to dine. The room was warm. Simon’s sherry was good, and so were his cigarettes and cigars. The guests sat in a widely-drawn semicircle, the centre of which was the fire: Simon apart in his leather chair on the right-hand side of the fire; Polly, his wife, deep in conversation with the newly-married young Mrs Olivier, whom she had pinned down on the settee for a talk about furniture; Jessica, Simon’s daughter, yawning over a magazine; Basil, his younger son, and Pauline, Basil’s wife, separate and silent, Basil because he was thinking of her, Pauline because there was no one near enough to talk to except him; and completing the semicircle, on another deep settee, James Gabb, Simon’s brother, and Hubert Olivier the lawyer.

‘You know,’ James was saying confidentially to Hubert – though the distance between them and the other guests made a lowering of the voice unnecessary – ‘I’m not at all sure Simon did the right thing in buying this great place.’

‘The right thing?’ echoed Hubert, giving the phrase a mocking twist, as if that were the last consideration that need apply. ‘What makes you think so?’

‘For himself, I mean,’ said James, ignoring Hubert’s misinterpretation. He glanced across at his brother sitting in his leather chair with his whisky and soda beside him, gazing into the fire, as much alone as if he were in his study ‘at home,’ as James automatically called it, meaning Simon’s previous residence.

‘I don’t see why,’ said Hubert Olivier in the richly-modulated voice which gave him so much pleasure: ‘It’s the finest property in the county, and it was going dirt cheap. Yet no one would look at it, because no one but Mr Gabb could have afforded to run the place. It had been on the market for nearly two years when Mr Gabb bought it, and already it was going to rack and ruin. Personally, I like to see these old places being kept up.’

James eyed him shrewdly. ‘Oh yes. And your firm handled the deal. I can well understand—’

Hubert lifted a pained white hand. ‘My brother William,’ he corrected.

‘Oh yes, your brother’s the solicitor. But it was you who put the business in his way. Don’t tell me you didn’t get your pickings!’ Hubert did not deign to answer. He disliked James Gabb, and was not much interested in him as a possible client. Simon was the quarry,and he was pleased to see how well Madeleine seemed to be getting on with Mrs Simon. But still, one never knew. Simon and James seemed to be on good terms, and the families were much interwoven. It would not do to quarrel with James.

‘No; what I meant was,’ James was proceeding, ‘this place is too big for Simon. We were born in a back street in Birmingham. Well, one’s ideas change, and neither of us would want to go back there, even for our own sakes, much less now we’ve got children who’ve been brought up quite differently from ourselves. But buying this place was going too far.’ He stared across the room, past the circle of heads, to the great windows that ran from floor to ceiling. It was still light enough to see the view, down over the terraced lawns and flower-beds to the lake that shimmered palely in the watery sunset, and the dark woods behind the lake. ‘It makes one feel small, sometimes, and that’s not good for a man like Simon, who’s always had to fight his way in the world.’

Olivier laughed patronizingly. ‘I don’t suppose he would agree with you.’

‘Perhaps not,’ said James. ‘He’s stubborn. But all the same, when he looks round at a set like this, all sitting primly in their places, ten yards from the fire, he must laugh sometimes. He must know they’d sooner be bunched up all together in the sort of room they’re used to, which would go about eight times into this one.’ He sat forward, hands on knees. ‘Look at ’em: do they look at home?’ He leaned back. ‘No, and they never will. In time they’ll get to hate the place. ’Tisn’t made for them.’ He rounded on Hubert. ‘Was it your brother,’ he asked bluntly, ‘or you, who advised him to buy the place just as it stood – furniture, pictures, everything?’

‘It was a great bargain.’ Hubert glanced round the room. ‘The dealers would have been glad if he had turned down the fittings, believe me. He would have had to furnish the place anyway. He saved thousands.’

‘Yes, but all these pictures, miniatures, knick-knacks and whatnot—’James waved a hand. ‘They belong to someone else still. He’s paid for them, but they’re not his. He’s living in a house of ghosts.’

Hubert said no more. A moment or two later he rose and crossed the room to talk to Simon Gabb.

James called out heartily to Pauline: ‘Well, my dear, and how’s the boy?’

‘Very well, thank you,’ said Pauline stiffly. Her bored expression did not change. Basil watched her broodingly. He thought what a fool he had been to imagine that motherhood would change her. She was bored with the baby too, because it was his. She was beautiful, stupid, shallow,cold-hearted, untouchable – the rich spoilt daughter of rich common parents, like his own.

‘Our parents are better than we are,’ he thought. ‘My father has talent, genius perhaps. He founded the great business on which we all live. My father is a master of men and of circumstance: if anyone got across his path, they would be removed. As for a woman: could anyone see Simon Gabb altering a single item of his daily routine to please his wife? And yet doubtless he loved her, and she obviously doted on him. Whereas I,’ thought Basil, ‘am my father’s employee, industrious, dependable, dependant. And as a husband, I am a joke, though so far a joke that only I have seen.’ He clenched his fists. ‘But one of these days, I’ll make them all change their tune…’

Madeleine Olivier had left Mrs Gabb’s side, and moved across to Pauline; for Mrs James Gabb had now come in, and was enthusiastically welcomed by Polly. The two ladies had much to say to each other. Madeleine therefore made her escape, and sat down beside Pauline. She and Pauline were old school friends.

Pauline, Madeleine thought, looked bored: more bored than ever, for her expression had never been very animated. It was clear that she was not very happy with Basil. Even the baby seemed to have made no difference; it had added to Pauline’s air of discontent. What was the matter? Madeleine wondered. Did Pauline find her position unsatisfactory, in spite of the wealth and the power of the family into which she had married? Perhaps the trouble lay just there: Pauline had stepped into the second place, by marrying the younger son; and the second place was not by any means her rôle. Not that she, or any sensible girl, would have preferred to marry Giles…

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.