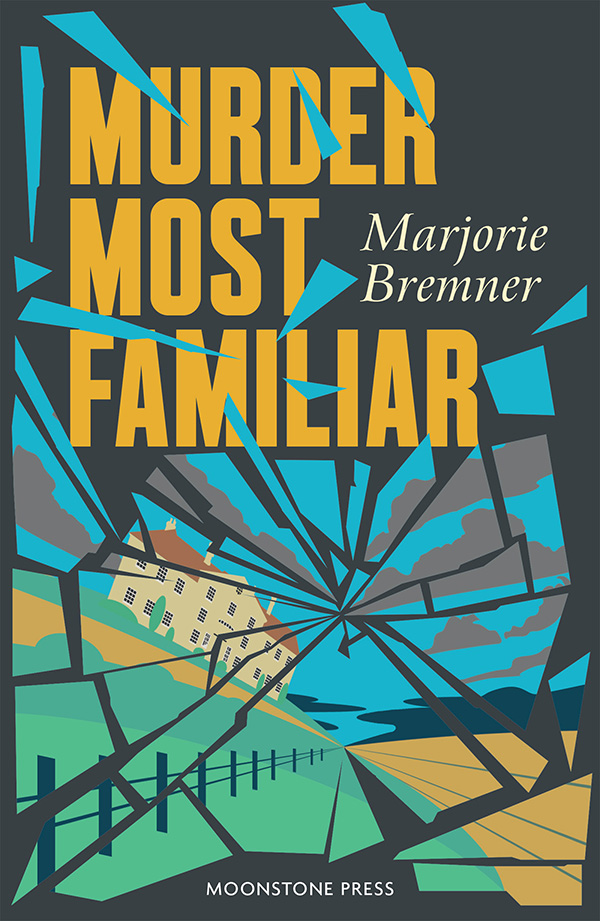

Murder Most Familiar

“A man does not leave school at fourteen, make a fortune by forty, and go on to become a skilful and powerful politician without ruthlessness.”

Business magnate and MP Sir Hugh Mason is the kind of man it is very easy to hate, if you are not susceptible to his particular kind of charm. He has of necessity hurt a lot of people on his way up. Taciturn and enigmatic, even his extended family do not know him well. At a weekend gathering for his sixtieth birthday, it slowly becomes apparent that Sir Hugh plans to give substantial funding and support to a new right-wing political group called the Freemen. But the next morning he is dead of poisoning, and the evidence suggests a family member must be responsible. But who among them would risk such a move, given that Sir Hugh provided for all?

Marjorie Bremner (1916–93) was born in the United States and educated at the University of Chicago and Columbia. A practising psychologist, Bremner was later in the US Naval Reserve and came to London in 1946 to work on a PhD in political science. She did research for the Hansard Society and became a freelance journalist and reviewer for Time and Tide and the Twentieth Century. She wrote two detective novels, Murder Most Familiar (1953) and Murder Amid Proofs (1955).

£9.99

By Marjorie Bremner

First published in 1953 by Hodder & Stoughton

Paperback

190pp

ISBN 9781899000487

Available June 2022

eISBN 9781899000494

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

My Uncle Hugh was the kind of man it was very easy to hate, if you were not susceptible to his particular kind of charm. He had of necessity hurt a lot of people on his way up, and he had learned to be tough. Perhaps he always had been and had no need to learn. A man does not leave school at fourteen, make a fortune by forty, and go on to become a skilful and powerful politician without ruthlessness.

My Uncle Hugh’s career, besides demonstrating his own competence, showed how far and how fast an entire family can be lifted in England in only one generation, by the efforts of one man. He was the second of four children. He came from a working-class home. None of his brothers or sisters—not William, nor Hugh himself, Mary, or my father, Max—stayed in school beyond their fourteenth birthday. No member of my family, before my own generation, had ever been well educated, kept a servant, been to the Continent, or been in a position to waste money or to indulge in luxurious tastes.

The photographs in our family album to-day tell a very different story. There are innumerable groups taken at Uncle Hugh’s estate,

Feathers. (From the album it could be assumed we spent a disproportionate amount of our time having tea in the garden.) There are pictures of the boys at Eton; of Daphne at school; of myself at school and at Newnham. We appear skiing, sailing, riding, and playing

tennis. There is an elaborate photograph of Daphne’s wedding at St. Margaret’s, Westminster; a snap of Charles, elegant and amused, as

best man at Andrew’s wedding to the Honourable Anne Durcott. And all this—the transition from the working class to Feathers and everything

that went with it—was done by just one man.

It was perhaps not the least part of his achievement.

It is, of course, education that can transplant an entire family from one class to another far higher in the social scale so quickly and with so

little pain. Uncle Hugh’s task would have been much harder, though, had it been necessary for him to take a large number of adult relatives

with him—or even his own wife. But she died in the third year of their marriage, leaving an only son, Charles. Uncle Hugh had two brothers and one sister. My father, Max, was his younger brother. He and my mother were killed when I was five, and Uncle Hugh took over my guardianship. The only girl of the family, Mary, married a man called Randall, had one son, Giles, and died giving birth to her second son, Timothy. Her husband succumbed

to an old war wound a matter of months later, and my uncle assumed care of the two boys as well.

So the only adults he took with him on his climb were his older brother, William, and William’s wife, Mildred. The couple had two children, Andrew and Daphne. My Uncle William had none of his brother’s ability. Nor did he have his charm, though he could on occasion produce a sort of bonhomie

which passed for personableness with the less critical. He developed a certain competence in the narrow field of accounting, though he was never able to think of finance or of economics in broad, general terms. He may have been of a certain amount of use to Uncle Hugh, and he was naturally devoted to his brother’s interests since his own were inseparable from them. But I do not believe Uncle Hugh relied on his brother’s judgment in any serious or complicated matters, and though he continued to give William more money and more prestige, William was never really important in the business.

My Uncle William was not a fool. I doubt whether he dwelt much, deliberately, on the differences between his brother and himself. But unconsciously—and sometimes even consciously—he must have been aware of them; and they must have rankled. I never heard him anything but polite to Uncle Hugh. But sometimes when only we children were about, he allowed himself the luxury of a sly dig or a piece of corrosive wit. I don’t know whether I really understood these barbed remarks at the time, or whether I only came to understand what Uncle William had meant as I grew up. Nor do I know whether Uncle Hugh was aware of his brother’s deep resentment and jealousy. Uncle Hugh was a man of considerable reserve, and I seldom knew what he was thinking, still less what he felt.

My knowledge of my Uncle Hugh’s deeper thoughts and feelings was not measurably increased by the years I spent with him as his personal assistant on the political side. (A man called George Tay had for years been his personal assistant in the business, a position which my Uncle William’s son, Andrew, had strong ambitions to fill.) These years began shortly after the war ended. My job, which had been interesting and exacting, finished with the war, and I had no idea what I wanted to do next. My Cambridge ambitions had disappeared in the wake of a brief (and unwise) marriage and the responsible job at which I had overworked for nearly three years. I had read political economy and history at Cambridge, and had always been interested in politics, so that on those grounds it was perhaps reasonable for my uncle to offer me the job. It was characteristic of him to do so though he knew I did not share his political beliefs; and characteristic of me, no doubt, that I took the path of least resistance—and the job.

Working with my uncle, I began to appreciate his great energy and his ability; and I came to understand the reasons for his success. It was not due to outstanding intellectual ability. He was intelligent, but I have met many men more able in that way. For sheer intellectual ability, both his son Charles and our cousin Giles surpassed him, and Andrew was probably his equal. Nor, though he had a good deal of rather blunt, personal charm, was it primarily due to personal magnetism.

But he had, coupled with energy and a clear mind, an undeviating steadiness and strength of will; good judgment and a good sense of timing; unimpaired self-confidence; the hide of a rhinoceros; and very few scruples. With that equipment, it would have been much more surprising if he had not been successful.

Working with my uncle proved over the years to be steadily and increasingly interesting. But it was demanding and wearing, and I welcomed the respites which sometimes came when Uncle Hugh decided to take one of his trips to the provinces without me. So I was not especially pleased when a last-minute change of plan, one Monday in the spring of 1952, made it necessary for me to accompany him to Birmingham at barely an hour’s notice.

Raikes, the chauffeur, who had been with us for about fifteen years, was driving. My uncle and I sat in the back, composing a speech which enthusiastically ascribed all our current difficulties to the past follies of the Labour governments. How much my uncle believed of what we were writing I am not sure: perhaps half, more probably less. But it was developing into an amusing speech and I hoped we would finish it before our first stop at Oxford, where my uncle had some affairs to attend to.

But we did not finish the speech. We were about ten miles from Oxford, doing sixty-five miles an hour on the main road, when the front tyre exploded with a roar. Raikes did the best he could, but the combination of speed and the heavy car were too much for him, and we left the road and turned over before coming to a stop in the ditch.

It was a nasty smash, and a very lucky thing we were not all killed. In fact, we got off very lightly. We all had cuts and bruises, and I had sprained my left wrist. That was all. The Automobile Association arranged for us to be taken to Oxford. Uncle Hugh there decided to continue his journey by train and to send Raikes back to London with me, in a hired car. Raikes arranged to meet him in Birmingham with one of our other cars, two days later.

I sat in front with Raikes on the way back. He was an extremely good chauffeur and he had taken great pride in the Daimler, which was fairly new. “I don’t understand it, Miss Christy,” he kept saying at intervals of about five miles. “Those tyres had just been checked. There was nothing wrong with them. There was no reason for that one to go. And there was nothing on the road I could see—no nails or glass—that could have caused it.”

I shrugged my shoulders. “These things happen every day. Don’t worry about it, Raikes. My uncle doesn’t blame you. Anyone can blow

a tyre.”

Raikes looked unconvinced. He had never had an accident before, and I think he considered a flat tyre a slur on his professional integrity.

I did not feel well enough to argue about it with him.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.