‘I must try not read this one too quickly otherwise I shall be compelled to pay a second visit to [you] today, just to borrow another book.’

— Customer to bookseller in Seven Clues in Search of a Crime (1941)

For most people this statement seems nonsensical – surely you buy books from a bookseller, not borrow them. There are libraries and there are bookshops and never the twain shall meet. But someone alive before WWII would recall a world where your local library was probably not a hush-filled citadel filled with acres of books — it was more likely a side business run by a bookshop, news agent, pharmacy or department store. Public libraries at that time were serious affairs focused on educational rather than recreational reading.

Rental libraries have existed for centuries. Book dealers often rented out some portion of their stock, and commercially loaned book sets were maintained by publishers, grocers, stationers or haberdashers. London publisher William Lane supplied merchants with boxes of complete circulating libraries with catalogues and instructions on how to sell them; they contained romantic novels published by his own Minerva Press and were very popular. By 1801, there were a thousand independent rental libraries in England. In 1842, Charles Edward Mudie opened Mudie’s Circulating Library, with the aim of providing the middle classes with access to literature. For an annual fee of one guinea, a member of Mudie’s was entitled to borrow one volume at a time. Mudie’s did not have open-access shelves; the books were chosen via a catalogue and brought to the reader by a library assistant or ordered by post. He also licensed retailers in resort communities as agents.

By the 1920s, better managed rivals W.H. Smiths & Sons and Boots the Chemist had taken over the market. News agent/bookseller Smith had acquired near-monopoly positions in British railway stations, and Boots was Britain’s major pharmacy chain. Both opened library departments in their stores and eventually reached a total of near ten thousand locations. They offered customers the convenience of returning books to any branch regardless of where

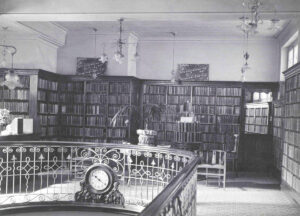

they had been rented. In the larger stores, Boots libraries were designed to emulate a private study in a comfortable country house. Positioned at the back of stores or upstairs, they were intended to increase store footfall, raise the image of Boots shops and attract a more affluent class of shopper.

To add to this cornucopia of lending, ‘twopenny libraries” targeting working class customers sprang up rapidly in British cities in the 1930s. They charged per book borrowed and required no deposit or ongoing subscription, and were frequently sidelines to existing buinesses to such as tobacconists and news agents. Larger retailers, including department stores opened library departments too. In his presidential address to the Library Association in 1938, W.C. Berwick Sayers observed: ‘We have the almost spontaneous appearance in thousands of shops of departments for lending light literature, so much so that it would seem the lending of reading matter is becoming an axuiliary of every business.’

A similar phenomenon occurred on the other side of the Atlantic – the late 1920s/early 30s saw the rise of libraries in drugstores, fueled by retailer efforts to increase footfall during the Depression. By 1935, Publisher’s Weekly estimated there were fifty thousand of these rental library outlets in the US compared to only ten thousand bookstores. Such was their prominence that American modernist author William Carlos Williams wrote a poem entitled “Drugstore Library” (‘That’s the kind of books they read/They love their filth/Knee boots and they want to hear it suck when they pull ’em out’)

After WWII, the rental library business began to decline in both England and the United States. Although television is sometimes blamed for this, the advent of inexpensive paperbacks and general prosperity were the main culprits. By the early 1950s the number of paperbacks published annually was four times the number of books pre-war. Mudie’s closed in 1937 and the circulating libraries of both Boots and WH Smiths closed their doors in 1966.