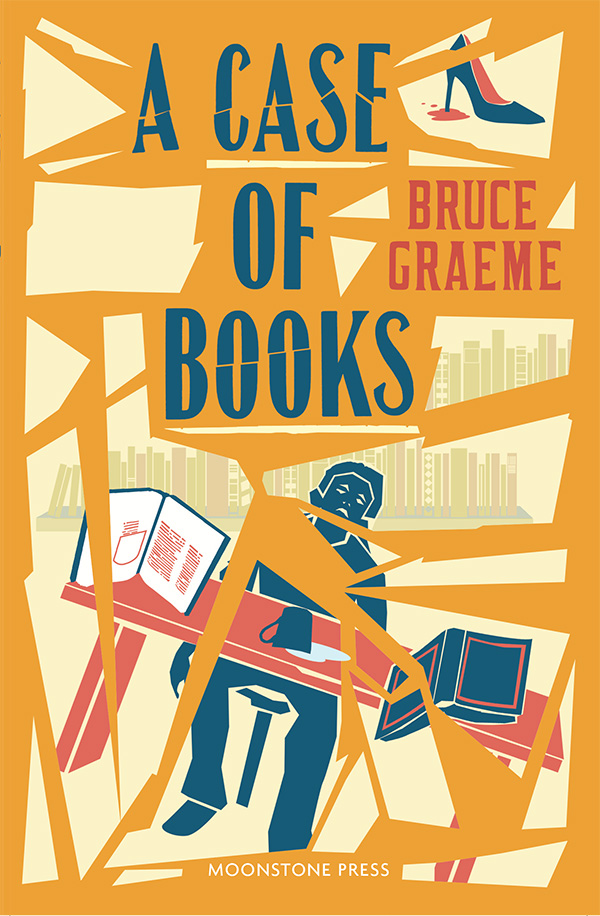

A Case of Books (1946)

In the beginning was the Word—

When Theodore Terhune’s wealthy client Arthur Harrison is found stabbed and his library ransacked, the police suspect the murderer was looking for a book. Harrison collected rare early printed books called incunabula, but as the provenance of such titles is well documented in the book world it would make little sense to steal one. Terhune is hired by the estate to sell off Harrison’s library, but another armed break-in and a very strange book auction suggest the killer is still searching for something. Soon Terhune himself becomes a target, but what exactly does the murderer want? And why are crosses appearing in the turf of local fields?

The sixth book in the entertaining series involving bookseller and amateur sleuth Theodore Terhune.

£9.99

By Bruce Graeme (pseudonym of Graham Montague Jeffries)

Introduction by J F Norris, vintage crime historian

First published in 1946 by Hutchinson & Co Ltd

Paperback

270pp

ISBN 9781899000364

eISBN 9781899-000371

Available December 2021

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Only rarely were both Terhune and Anne Quilter absent from the shop, but it did happen occasionally, and the last Tuesday in May chanced to be one such day.

It was less unusual for Terhune to be away; it was his custom, on the last Tuesday of every month, to visit London to select and buy the latest publications, and to negotiate other sundry transactions with buyers and sellers of second-hand, rare, and antiquarian books. So, usually, Anne’s was the sole responsibility for carrying on that day’s business in the shop at Bray-in-the-Marsh. But the inexorable law of averages, which prevents any series of events from being one hundred per cent trouble-free, this exasperating, intangible, natural law made its power felt on the last Monday in May, that is, the day before Terhune was due to pay his monthly visit to Charing Cross Road, and sundry roads west. Anne, cycling back to her work after the midday meal, was knocked down by a skidding car.

Fortunately, she was not seriously injured. But Doctor Harris had ordered her to remain in bed for the remainder of the week, so Terhune had quickly to arrange for Miss Amelia to act as Anne’s substitute.

The indirect consequences of Anne’s unfortunate accident were first brought to Terhune’s notice just one week later, by which time Anne had returned to work, none the worse, apparently, for her mishap.

Shortly after four-thirty p.m., a small Austin pulled up in Market Square, just outside Terhune’s shop. Through the glass-panelled door he saw a woman emerge from it, and cross the pavement with the very obvious intention of entering the shop.

She was a stranger; he inspected her with all the curiosity of the countryman in whose village complete strangers are rare. She was tall, slim enough for her thirty-odd years, a false blonde, pleasant-looking, but dressed in clothes which bore the hallmark of the inexpensive chic of suburbia.

The door opened; she entered with a purposeful stride, and moved across to Anne’s desk, which stood before the lending-library shelves on the left.

Anne smiled a welcome. “Good afternoon, madam.”

The woman snapped: “Good afternoon. Who owns this shop?”

“Mr. Terhune, madam.”

“Is he available?”

“He is at his table over there, madam, towards the back.”

The newcomer swung round, saw Terhune, and made towards him. Suspecting trouble he rose quickly. “You wish to speak to me?”

“If you are Mr. Terhune, I do.” He smiled disarmingly, and indicated the chair which stood beside the desk.

“Won’t you sit down?” She sat down, unbendingly. “My name is Mrs. Rowlandson. Less than two weeks ago my husband and I moved into this neighbourhood.

From London,” she added with a note of condescension. “We have purchased Willow Bend.”

Terhune nodded. He knew Willow Bend, a small, but rather charming house, standing on the Toll Road, about half a mile south of Wickford. Its late owner, a man named Jellicoe, had died earlier in the year, since when the house had been empty.

“We have only been married a few weeks,” Mrs. Rowlandson continued. “Until last year I lived abroad with my parents, in a country where domestic labour was cheap, so you will realize that I have not been accustomed to doing housework.”

Terhune could make neither head nor tail of the reason for this long explanation; but he murmured politely: “Of course.”

She continued: “Last Monday afternoon, as I was passing through Bray, I caught sight of your shop. I thought it might be a good idea for me to buy a book on household hints, so I called in.” Mrs. Rowlandson paused—whether for dramatic effect, or whether to give her the opportunity of regarding him accusingly, he didn’t know. He smiled wryly; he suspected that Miss Amelia had been up to her tricks again—the poor old dear was so incredibly willing, so desperately anxious to please everybody.

“There was a woman here. Not a young woman—” A slight movement of her blonde head indicated Anne. “An elderly female. With teeth—”

“Miss Amelia,” Terhune murmured. “I am not in the least interested in her name,”

Mrs. Rowlandson snapped. She stared angrily at him. “I suppose you know your business, Mr. Terhune.”

“I have been a bookseller for several years,” he informed her modestly.

“Then your past experience does you no credit.”

He did not dare glance at Anne; he had a vague idea that she was making rude faces at Mrs. Rowlandson’s back—Anne was still very young!

“You met Miss Amelia?” he prompted.

“I did, indeed. To my cost, I might say. Believing that this was an efficiently run establishment I asked for a book on household hints. Do you know what that—that stupid woman sold me?”

He tried to think of titles in stock. “Elizabeth Hallett’s Hostess Book, or Enquire Within?” he suggested, not very hopefully. Then, as an afterthought: “Not the eight volumes of Every Woman’s Encyclopedia?

A little old-fashioned, for these days—”“not Every Woman’s Encyclopædia,” she interrupted firmly. “The book I purchased, stupidly without first examining it, was entitled Vinegar and Brown Paper.”

The sound of a muffed explosion came from the direction of Anne’s desk. Terhune choked. Painfully! Vinegar and Brown Paper was a lighthearted novel by John Paddy Carstairs, as far removed from sweet domesticity as the moon from green cheese.

“I am very sorry,” he began. “It was extremely stupid of Miss Amelia. She should have been more careful—”

“You have not heard all,” Mrs. Rowlandson interrupted again. “That foolish woman sold me another book by the same author which she claimed was a cookery book.”

A cookery book by John Paddy Carstairs! Anne made a dash for the door, and disappeared. Terhune stared aghast at his visitor while he tried desperately to remember the author’s titles, and identify Miss Amelia’s second faux pas. Presently a horrible thought occurred to him.

“Not—not Curried Pineapple?” he gasped.

She nodded, and his self-control collapsed. Soon he could see Mrs. Rowlandson only through a mist of tears. Curried Pineapple a book of recipes! Ye gods!

Presently he recovered; but he had to take off his horn-rimmed glasses, and wipe the lenses dry, while he gazed anxiously at his visitor.

“You must forgive my rudeness,” he pleaded. “Please!”

Then he saw that her eyes, which he had thought were so frostily blue, were twinkling.

“I’m not really cross, Mr. Terhune,” she told him. “Even though I have only lived in the neighbourhood for a few weeks I’ve heard all about Miss Amelia. Poor dear! I think she’s so sweet. Isn’t she rather good at fine needlework?”

“I believe so.”

“In that case I hope she will be able to spare me an occasional afternoon. But there, I didn’t really come here to complain or talk of Miss Amelia, but to ask—” She paused, to smile confidingly at him. “Have you any other books by that author I can borrow?” He made a move.

“And some genuine household and cookery books?” she added, “One or two Elizabeth Craigs, perhaps?”

A little more than fifteen minutes later, Mrs. Rowlandson left, withan armful of books. As the door closed behind her the telephone bell rang. Terhune picked up the receiver,

“Hullo.”

“Mr. Terhune?”

Terhune thought he recognized the matter-of-fact, vaguely Irish voice of Detective-Sergeant Murphy, “Speaking, sergeant.”

“Are you busy at the moment, Mr. Terhune?”

The question produced a delighted grin on Terhune’s round, healthy face. A grin not of amusement, though it might well have been, seeing that he had done no more strenuous work during the past hour than sell the latest Philip Hughes to Isabel Shelley, and a mixed selection of books to Mrs. Rowlandson. No, the grin was one of slightly heartless—but very human—excitement: Murphy wasn’t in the habit of ringing up during Terhune’s working hours unless something unusual had happened.

“No,” he replied eagerly. “Why?”

Murphy did not answer the question. “Would you care to come over to Twelve Chimneys?” he asked instead.

Twelve Chimneys! A house well-known to Terhune, for it was the home of Arthur Harrison, an ardent—and wealthy—book-collector. During the years he had lived at Bray-in-the-Marsh Terhune had sold many rare books to Harrison. Fairly recently Harrison had paid him £40 for a copy, in excellent condition, of Bode and De Groot’s Complete Work of Rembrandt, and a similar amount for a rubbed copy of Saxton’s Atlas of England and Wales, published in 1579.

The shadow of misgiving succeeded excited interest. “Nothing’s happened to Harrison, sergeant?”

“I’m afraid something has, Mr. Terhune,” Murphy replied evenly. “He’s been killed.”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.