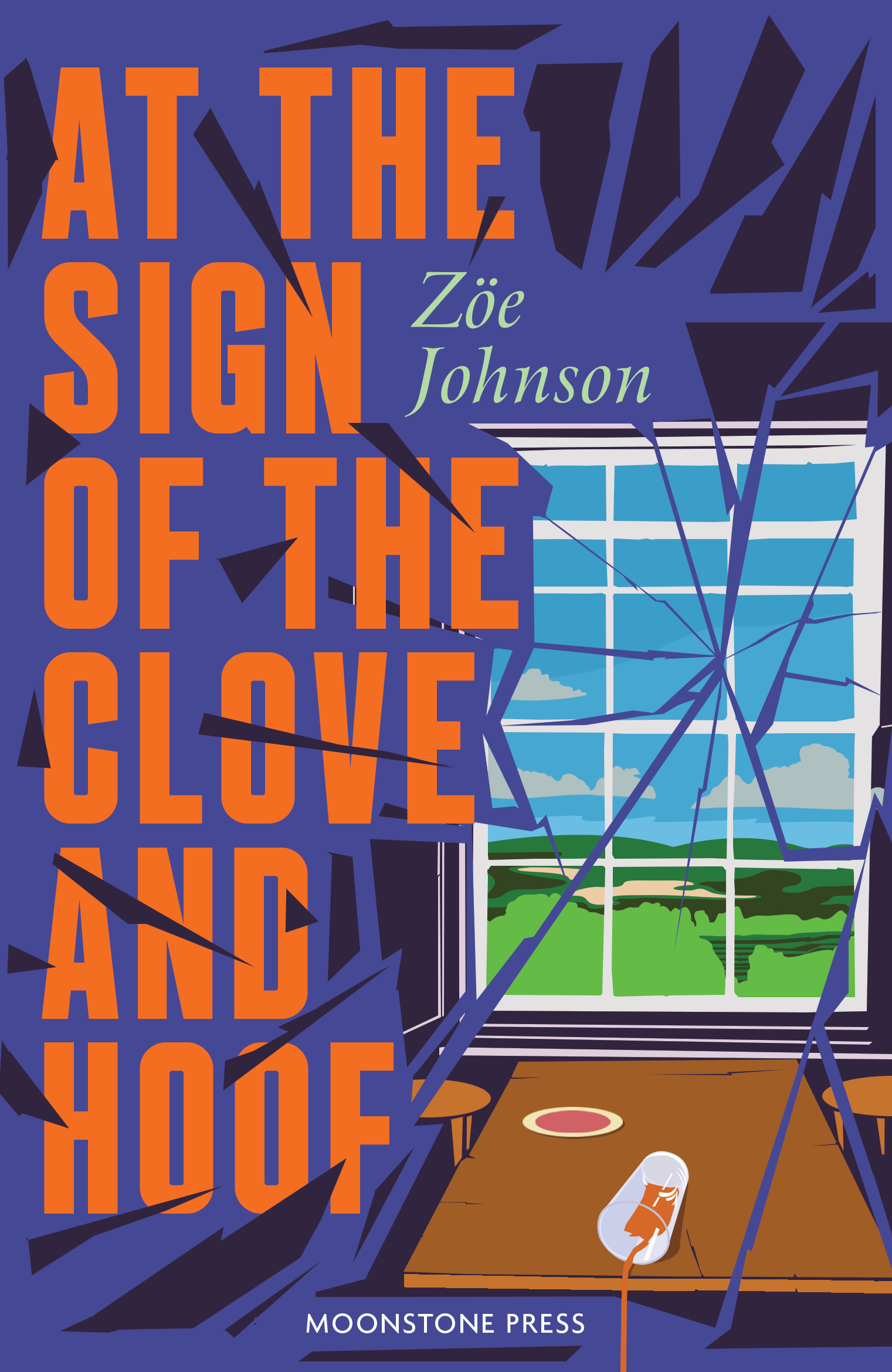

At the Sign of the Clove and Hoof

“This letter has come straight from the murderer, don’t you realize that? Hot from his bloody hand. Don’t just stand there dithering, man. Don’t you realize you hold the key to everything?”

The Clove and Hoof is the hot spot in Larcombe for a pint of bitter, a good story and some laughs. It’s also the focal point of a bizarre series of murders, for the only connection the victims have seems to be that they all frequented the local pub. Strange pranks, a spate of anonymous letters all painted in blue watercolor, and a decapitated head found floating in the stream near Starehole Gap all lead to the police uncovering unusual criminality dating back 20 years. Two policemen with decidedly differing approaches to crime solving head up the professional side of the investigation, accompanied by Christian Peascod, dilettante of the arts and amateur detective.

£9.99

By Zoë Johnson

First published in 1937 by Geoffrey Bles

Paperback

256pp

ISBN 9781899000562

eISBN 9781899000579

Available April 2023

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

And so, in conclusion, I would urge those of you whose faith has been so lukewarm in the past as not to play a prominent, nay, a paramount rôle in the life of every day, to turn afresh and lift…”

The Vicar of Larcombe always read his sermons, but as a concession to such members of his flock as looked for more spontaneity and direct inspiration in his teaching, he was in the habit of raising his eyes from his book at intervals of about three minutes, to show that his congregation was not entirely out of his mind. At the word “lift,” he shot one of his customary glances into the body of the little church and in doing so, his eye, his watery eye, took on an expression of, at once, great surprise and indignation; surprise that there should be a stranger present and indignation that the stranger should be asleep.

In the second pew from the back was a man; a very big, broad man with a square, pink face; he was wearing a dirty raincoat and his face was happy as he slumbered.

The Vicar frowned and proceeded “… your faces to the Lord, seeking the Light.”

The choirboys hurriedly stopped their Noughts and Crosses. With a sharp click of her false teeth, Mrs. Busby the butcher’s wife shut her mouth which she invariably kept open throughout the sermon, and nudged her husband for no reason at all. Under the schoolmistress’s inexpert, podgy fingers the ancient organ gave its preliminary cough and set about wheezing the final hymn.

As the Vicar stepped down from the pulpit, the whole church seemed to rustle in anticipation, and it was this rustle that woke the sleeper in the second pew from the back. Evensong was at an end. The handful of glum worshippers, uncomfortable in their Sunday starch and polish, shuffled out with whispering and creaking into the bleak September drizzle.

The little vestry of Holy Trinity was ill-lit and cold and damp, and it reeked of the carbolic soap which Mrs. Fitzroy lavished on its bare boards. With his mind on the remaining blank spaces in Torquemada’s Cross-Word Puzzle and the outstanding half of a bottle of whiskey, the Rev. Ernest Pratt swiftly unvested and hurried out into the rain. But a little old man with the voice and cheeks of a child was waiting for him; it was Sam Bowle; he doffed his hat and said, “Beg pardon, sir, I was wondering if you could spare a minute for our poor Dick. He thinks he’s going to die and he wants to see you bad. Would you mind, sir?”

The Vicar made very little effort to conceal his disappointment.

“Is it as serious as all that?”

“Well, you can’t rightly say, sir, with our Dick being like what he is. Dr. Girdwood has been saying he might pop off any minute for these last three years. But he wants to see you bad, sir; he does, indeed, sir.”

“Oh, very well.” The Vicar pulled his blue raincoat tightly round his throat, pushed the brim of his clerical pork-pie low over his eyes, and strode off down the hill, his trouser-legs flapping, his shoulders hunched, while poor Sam, almost at a trot, tried to keep up with him and to draw him out with talk of Alan Charnock’s new boat and the forthcoming marriage of his own cousin Lil at Setterham. But the Rev. Pratt maintained an ungracious silence all the way down the hill and seemed to find solace only in squinting down the long length of his rheumy nose.

Before his unfortunate illness, the invalid Dick Bowle had been remarkable in Larcombe for two things; the excellence of his private blends of tobacco (especially his justly-popular “Rich and Strong” at 6½d.) and his extreme sensitiveness as to the baldness that had come upon him with such suddenness. For his seven hairless years he had worn a bowler hat every minute of the day; there were rumours, even then, that he wore it in bed—but now that he was bedridden, Larcombe knew that it was so.

Practically everyone in the village had been to visit him at some time or other, and they had seen it, this ripe old bowler perched on his long, flat head, and they were, in a way, proud of their tobacconist who had thus distinguished himself. The clergyman frowned and pursed his lips as he came into the sickroom. Old Dick was sitting propped up against soiled pillows on his crude, brass-knobbed bedstead and wearing a seaman’s blue sweater for a bed-jacket; between his teeth was a short-stemmed clay and the air was blue with the smoke of thick-twist; the patchwork quilt was littered with sheets of a sporting, sensational Sunday newspaper.

The old man removed his clay and waggled it in welcome, indicating a rush-bottomed chair from which brother Sam hastened to remove a teapot and a tin of sardines. Pratt sat down on the very edge of this chair, locked his fingers together and cracked his knuckle-joints. He always performed his visiting-duties perfunctorily and unsympathetically, and he ministered to the incongruous Dick with especially bad grace. This time, however, he was shaken out of his uninterested mumbling.

“Did you notice that big, red-faced man in church to-day, sir?” enquired Sam during a lull in the Vicar’s drone.

“Yes, I did. The wretched fellow was asleep. Who is he?”

“I dunno proper,” replied the tobacconist’s brother. “He only come this morning. But they were saying at the Cloven that he were a detective from London.”

If Sam had announced that the Vicarage was on fire, he could not have surprised and distressed the clergyman more. For a moment, Pratt sank back on his chair without saying anything, his watery eyes dilating and his thin, knobbly throat giving out pitiful clucking sounds. Then he got to his feet and mutteringsome-thing about a letter to get to the post, shot out of the house.

A very surprised Sam watched him round the quay and set off up the hill towards the Vicarage, half walking, half running. Sam went back to the bedroom.

“I never could abide that man,” he said.

Old Dick cackled. “Now, now, you mustn’t be saying these things. He’s a minister, ain’t he? Ministers, I reckon, is not like other folk. Ministers ’as their own ways of doing. And I must say, Sam boy, yon’s done me a power of good. Yes.”

“You’m be a bit better then?”

“Surely. Them Bible-things is fine stuff.”

Dick’s clay was drawing again and he reached for a sheet of his newspaper. But his brother shook his head.

“He’s a crabbid old bouncer. I’ve always said so and I always will. What’s he want to go galumping off for like that?”

“Brew a cup o’ tea, Sam boy,” said Dick, deep in the report of a divorce case.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.