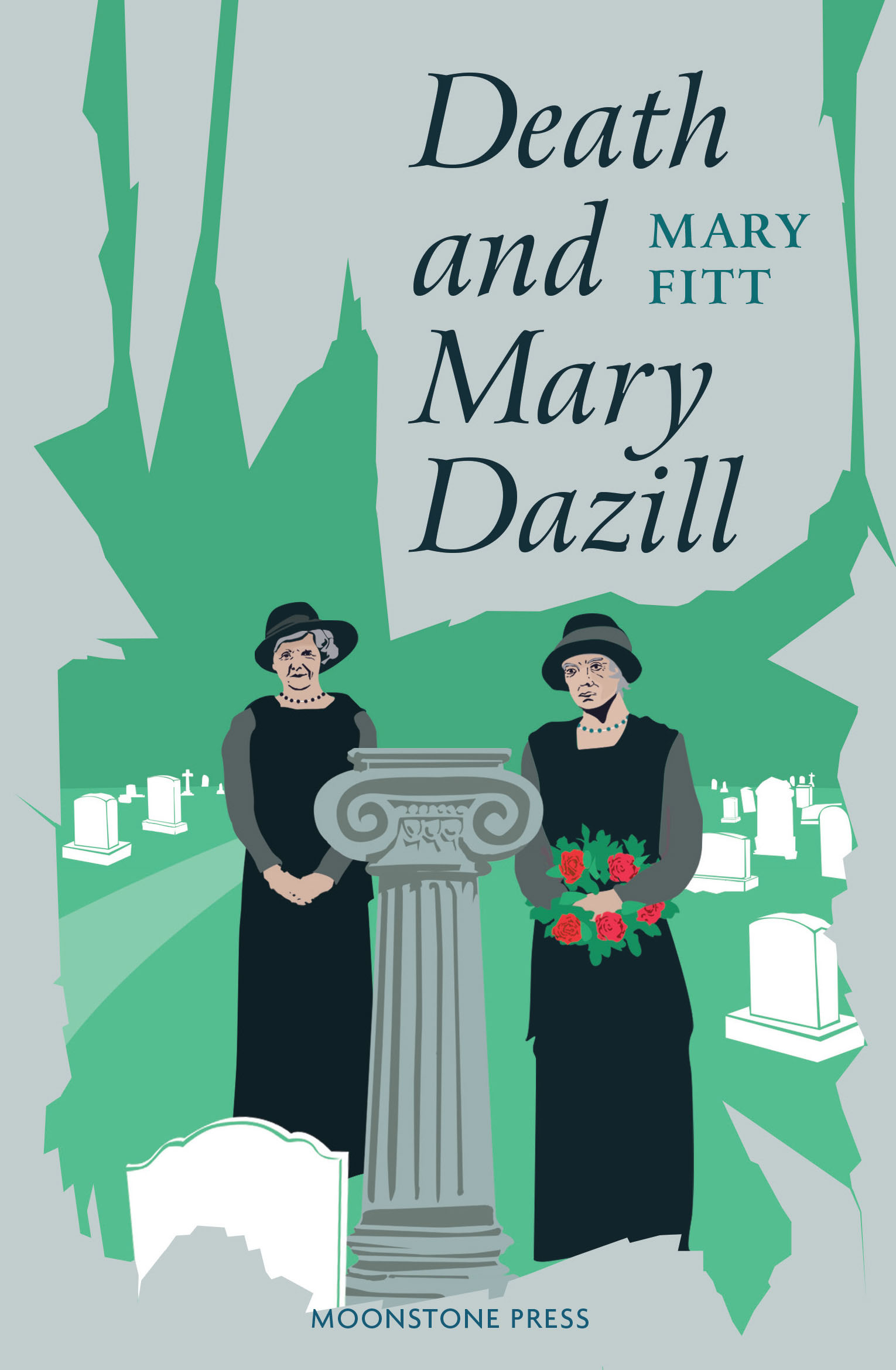

Death and Mary Dazill

‘Is it wise to evoke these memories—to raise these ghosts—after all these years?’

After attending a burial in an old country churchyard, Superintendent Mallett and his friends are struck by the sight of two elderly ladies, regally dressed in black and accompanied by their uniformed chauffeur, placing an elaborate wreath on the graveyard’s most imposing monument. The vicar confirms that the Misses de Boulter of Chetwode Lodge have placed fresh flowers on the tomb of their father and brother every week for the last fifty years. In the opposite corner of the churchyard lies the small, neglected grave of one Mary Dazill. In flashbacks, we learn how everything goes wrong in the lives of the two sisters when their father brings the enigmatic Mary home and proposes to marry her. Soon, murder ensues, and a fatalistic mystery with the emotional echoes of a Greek tragedy.

Mary Fitt was the pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman (1897–1959), a classical scholar who taught Greek at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire in Cardiff. Beginning in 1937, Freeman wrote twenty-nine mysteries and a number of short stories as Mary Fitt, and was elected to the Detection Club in 1950. Aside from her detective novels, Freeman published many books on classical Greece, scholarly articles and children’s stories. She lived in St Mellons in Wales with her partner Dr Liliane Marie Catherine Clopet, a family physician and author.

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1941 by Michael Joseph Ltd

Paperback

190pp

ISBN 9781899000500

eISBN 9781899000517

Available July 2022

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

The three men—Superintendent Mallett, Dr. Fitzbrown and Dr. Jones—turned away from the grave, into which the workmen had begun to shovel the heavy yellow clay mixed with stones. It was a drizzling afternoon in November. They had come across from Chode to attend the funeral of the local police-sergeant; and the ceremony in the little grey church, smelling of damp stones, and at the graveside in the misty rain, had lowered their spirits considerably. Even the post-funereal ham and whisky were, for once, lacking: the dead constable seemed to have no relatives. They threaded their way among the graves, across the wet grass towards the gravel-path. Mallett and Jones, walking in single file, kept their eyes fixed on the ground; but Fitzbrown stopped occasionally to read the name on a tombstone. The other two reached the path before him: there the Vicar of Long Marley awaited them.

‘A dreary afternoon,’ he called out cheerfully. ‘You fellows must come back and have a cup of tea with us.’ Then, as they demurred: ‘Oh, come, come! My wife’s expecting you.’

He made off down the path toward the lych-gate; Mallett and Jones followed him resignedly. As the Vicar reached the lych-gate, two tall old ladies entered: he swept off his hat to them, and paused for a moment to speak to them. Mallett and Jones slackened their pace, and, unwilling to be drawn into the encounter, stopped as if to wait for Fitzbrown.

The two old ladies, after a few minutes’ gracious conversation, bowed to the Vicar, or rather inclined their heads like two queens, and passed on. They were followed at a respectful distance by a chauffeur in wine-coloured livery: he stopped when they stopped, and moved when they moved, keeping exactly the same distance between himself and them, as if drawn by an invisible wire. He carried an enormous circular wreath of hothouse flowers: arum lilies, scarlet amaryllis, gardenias.

The little procession swept past Mallett and Jones, leaving the heavy scent of the wreath hanging on the November air. The two men, a little curious by now, watched them as they turned off up a side-path and halted in front of an enormous piece of statuary, the most conspicuous object in the whole churchyard, a broken column of white marble, on a pedestal, with, in front of it, a railed-in ‘garden’ of white chipped stones.

The two old ladies, upright as the marble column, and in their black clothes just as conspicuous, took up their stations one on each side of the low railing, while the chauffeur, at a gesture from one of them, placed the wreath at the foot of the pedestal. All three stood for a moment as if to attention; then the procession returned along the way it had come. Mallett and Jones stood on one side to let them pass by. Fitzbrown had now emerged on to the path. The other two watched him as he crossed it, and, to their surprise, went over to look at the massive marble tomb with its new ornament of flowers. He bent down, hands on knees, to look at the inscription… A few minutes later he joined them.

‘I should have thought you saw enough of corpses without wanting to pursue them below ground,” grumbled Dr. Jones. ‘When a man’s dead, he’s dead.’

Fitzbrown stamped, to get the clay and grass off his boots. ‘But his soul goes marching on,’ he said, ‘or rather, his memory, if you prefer. Sometimes, that is.—Did you notice that little ceremony going on away back there just now? Intriguing, wasn’t it?’

‘Pooh,’ said Jones, ‘you don’t mean to say a man’s continued existence, or even his “memory” as you call it, depends on the size and price of the wreaths his relatives lay on his grave?’

‘Not exactly,’ said Fitzbrown. ‘For all I know, one of these graves that nobody bothers about, with no name on it or just a headstone with a name, may contain the earthly envelope of some immortal mind or idea. But—when you see an enormous wreath being laid on a tomb, you assume that the person’s recently dead, don’t you? Well, I went to look at the inscription on that one—and you may be surprised to hear, the last person was buried in itnearly fifty years ago.’

‘H’m,’ said Mallett. ‘Pretty good. What was the name; did you notice?’

‘De Boulter,’ said Fitzbrown. ‘There were two inmates—father and son. The son died first, aged twenty. The father died just six months later, aged forty-six. Things like that always set my mind working. One scents a story. It’s an odd name, too. But this churchyard’s full of odd names.’

They had reached the lych-gate. The Vicar was waiting for them. He had just, apparently, replaced his hat after waving farewell to the two old ladies, as their long black saloon car moved softly away. The Vicar stood gazing after them for a moment, as if reluctant to see the last of them. He turned, however, with renewed gusto to his three guests.

‘This way, this way,’ he said, ‘just across the road. The samovar, and Mrs. Barratt, will be waiting.’

The vicarage sitting-room smelt of old books and tobacco, and not a little dust. But it was comfortable. There was a blazing fire, and deep chairs for all. The Vicar’s wife beamed, and encouraged her husband to tell stories. Gradually the three visitors thawed, stretched out their legs and felt at their ease. Pipes were lighted, and a silence fell. Mrs. Barratt, having served her purpose as dispenser of tea and toast, was about to leave them, when a sudden question from Fitzbrown arrested her; though it was to the Vicar, and not to her, that he spoke.

‘Who were those two old ladies with the lily-wreath?’

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.