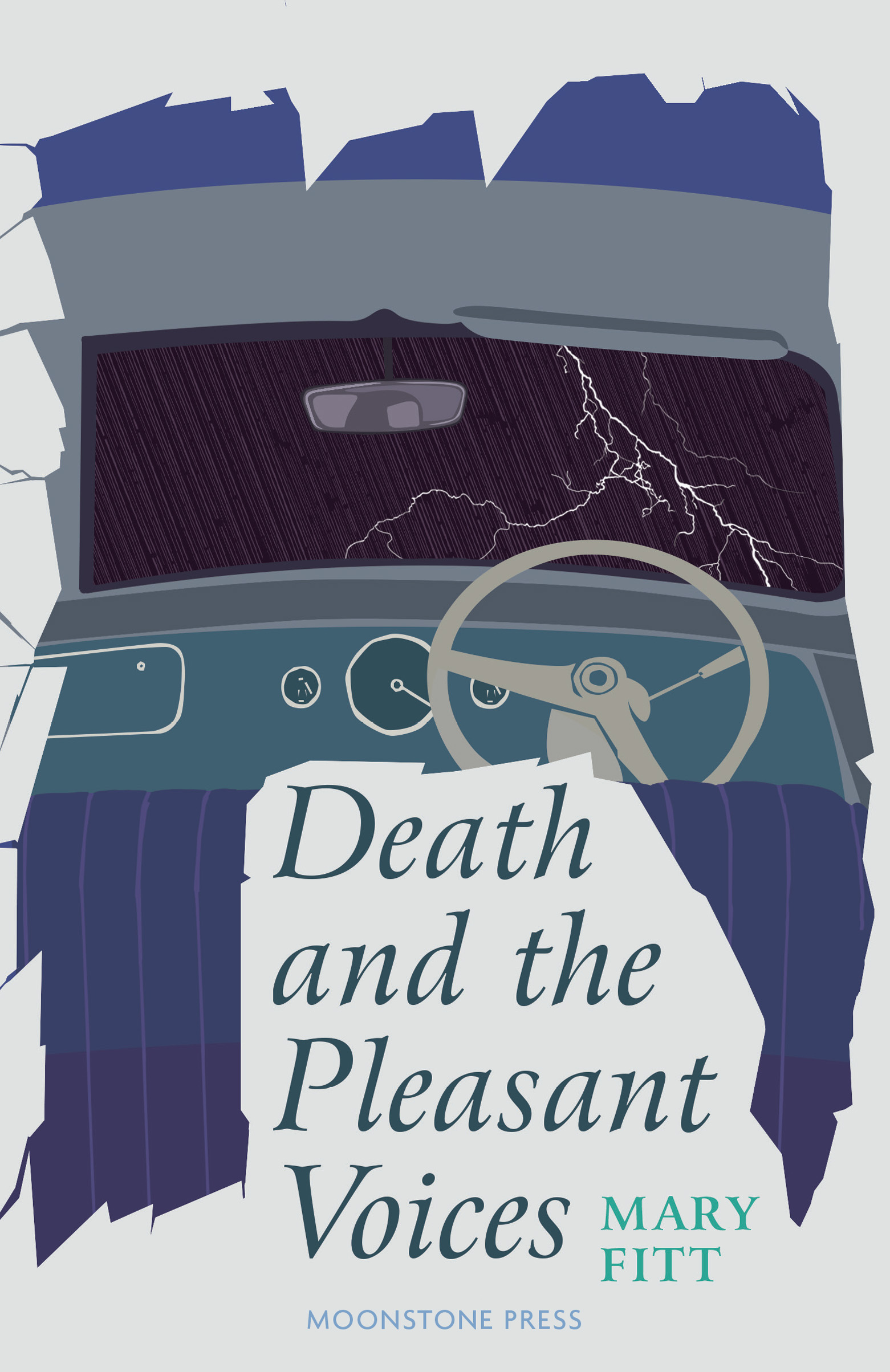

Death and the Pleasant Voices

‘All these people who thought themselves securely in possession for the rest of their lives are now going to be dependent upon the caprice of this young man.’

During a blinding rainstorm, Jake Seaborne takes a wrong turn and arrives at Ullstone Hall, where is he is initially mistaken for ‘Hugo’, the new heir to the family estate. It seems Hugo is the offspring of the late Mr Ullstone’s first marriage in India, but the children of his second marriage have never met him. In short, the Ullstone family destiny is now in the hands of a complete stranger. A friend, Sir Frederick Lawton (who, it turns out, knows Jake’s family) has been asked to act as a ‘sort of buffer’ for Hugo on his arrival, but Sir Frederick cannot stay and Jake agrees to act in that role until he returns. But not everything is as it appears, and when the handsome and charming Hugo arrives the next day, trouble follows and before long three people are dead.

Mary Fitt was the pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman (1897–1959), a classical scholar who taught Greek at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire in Cardiff. Beginning in 1937, Freeman wrote twenty-nine mysteries and a number of short stories as Mary Fitt, and was elected to the Detection Club in 1950. Aside from her detective novels, Freeman published many books on classical Greece, scholarly articles and children’s stories. She lived in St Mellons in Wales with her partner Dr Liliane Marie Catherine Clopet, a family physician and author.

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1946 by Michael Joseph Ltd

Paperback

190pp

ISBN 9781899000548

eISBN 9781899000555

Available October 2022

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

I have never seen such lightning or such rain in all my life. As I drove, the rain swept towards me in great grey sheets, so that the macadamed road was awash, and the lightning danced in quivering perpendicular lines just ahead of me. I cowered behind my low windscreen as if to avoid a blow; and over the sound of the engine I could hear crash after crash of almost continuous thunder.

The sky behind, before, above, closed down over me; it was far darker than the surface of the road. Unable to think, and scarcely able to see, I steered along, doggedly and slowly, wondering what it would feel like when the inevitable happened and the car was struck: is there, or is there not, a moment of awareness before death and oblivion, even when the manner of death is so complacently said to be instantaneous? I wondered then, and I wonder now. I came to a fork, and took the right-hand road. There was no means of knowing which was the correct one; the only thing to do was to go on. I had not gone more than a mile when I realized that I must have chosen wrongly: this was no longer the macadamed surface of the main road – itself a very third-class road with an enormous camber at each side, such as they still have in the country, where carts come before cars and drainage before safety – this was a lane, with a fairly good but untarred surface, one of those delightful lanes which are the same red colour as the ploughed fields behind their hedgerows. There was no room to turn; there was a ditch and a steep bank on either side, and the ditches, like the lane, were running with water. One could do nothing but press on in thehope of coming to a gap or a gateway, or perhaps a house or farm where one could take shelter. I pressed on, therefore; and I was not made happier to find that I was now coming into an avenue of immensely tall elm trees. I knew all about the dangers of elm trees in a storm. The dark green tunnel swallowed me up; it seemed to shut out some of the lightning, though the thunder still crashed unrelentingly overhead. And then, with a sputter and a sigh, my engine died.

I got out. It was useless to attempt repairs, useless to open the bonnet even, while the rain streamed down, making bad worse. I pulled up the collar of my storm-coat, and bowing forward, began to walk on along the lane, the elms groaned and creaked and soughed. The lush dark green grass in the hedgerows was uncut and thick with chervil, and the ditches ran gurgling like mountain streams. I could not believe that this lane led anywhere; and certainly there was no hope that any other motorist would pass this way and rescue me. Yet for some reason, or none, I did not think of turning back.

I went on, as one does sometimes, sure that it was the right thing to do, though I could not have said why. I was not altogether surprised, therefore, when I came to a wide opening: a curved gravel space leading to a gateway, two tall moss-grown pillars with animals on the top – monkeys, I saw they were, at a second glance, and thought what a curious choice – and, wide open, the two halves of most exquisitely wrought iron gates, all tendrils and vine-leaves and bunches of grapes, with a touch of rather faded gilding here and there. The gateway was set sideways, not parallel to the lane, so that one saw the open halves of the gate against a background of green shrubbery. There was no lodge; but the drive curved round invitingly, between rhododendrons and pines. Again, without hesitating or even making a conscious decision, I went forward as though the gates had been opened for me. In fact, I realized later to my amazement, I did behave and feel exactly as if I had been expected.

When I came to the end of the drive, though, and the long mansion stood before me, I thought at first that it looked deserted. Certainly in these times it could not be wholly inhabited. It was not beautiful, or handsome, or even very old; but it was imposing. It was built of some dark grey stone, and no imagination had been wasted on its design. It was simply a massive oblong structure with four tiers of windows, those on the ground floor being the longest and most ornamented, and those at the top the shortest; round the roof ran a stone balustrade. But there was no sign of life: no chimney smoked, and many of the windows had their white blinds drawn, giving the whole place an eyeless look. Standing there on the broad terrace, I thought that the place looked forbidding and forlorn, but, on second thoughts, not deserted: the lawns below the terrace were beautifully kept, the hedges were trimmed, the gravel of the drive was clean and weedless. And anyhow, I could not go back.

Again I bowed forward and pushed on, round the side of the great house, past a group of massive cypresses, to the front entrance, and with some misgiving, climbed the stone steps to the pillared porch. The brass handle of the iron bell-pull was highly polished, yet when I pulled it, it hardly seemed to move, and I had little hope that it would work. But in a very few moments, slow footsteps approached, the door was opened, and before I had time to formulate a question that would account for my presence, I found myself handing my coat to a man-servant, and following him across the hall, wiping my wet hands as I went. He asked no questions, not even my name. He seemed to expect me and, wondering, I accepted the role.

The door he held open for me was the door of the drawing room. I took it in at a glance. It seemed to me to be a very large room containing several groups of people dressed for dinner; but my impression was vague, as I stood there still trying to dry my hands on my handkerchief, for I was dazed by the storm, and the thunder reverberated in my ears. They had all been absorbed in conversation until I entered. Then they all turned and stared, in away that struck me as unusual, although I was a stranger who had no right to be there. Their looks were hostile and forbidding, like that of the house – so much so that I withdrew a step in surprise. Then a fair-haired young woman in a yellow frock detached herself from the group standing near the fireplace, and came forward with outstretched hand and dazzling smile.

‘Good evening,’ she said. ‘What a terrible storm, isn’t it? We thought perhaps the train would be late. I’m afraid you are rather wet. Did the car miss you? By the way, I am Ursula.’

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.