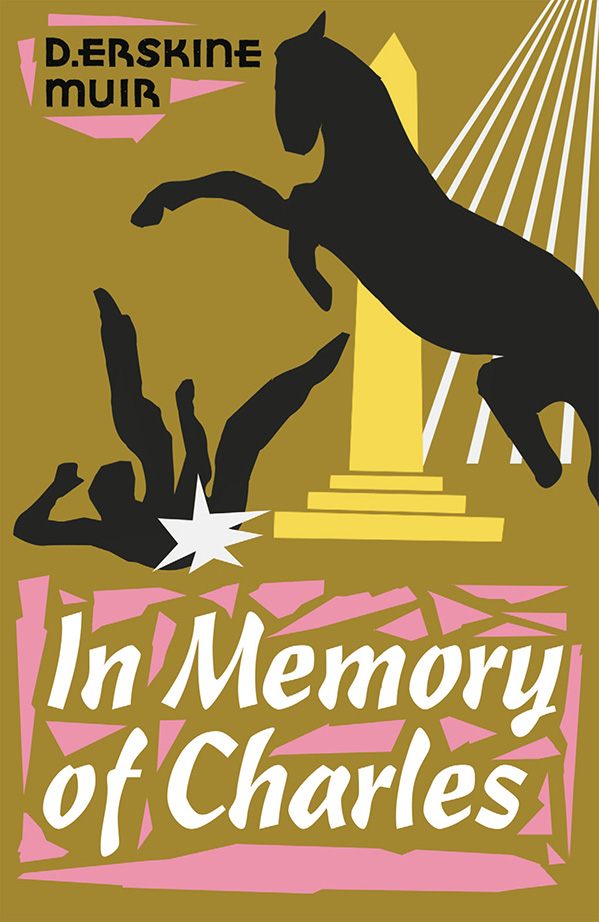

In Memory of Charles

Charles, according to all accounts, had clearly been boiling up to be murdered.

Charles Courtley was a difficult man. Prone to violent outbursts and a bully to his wife and daughters, he had uprooted his unhappy family from London to a country house in remote East Anglia. Wealthy and increasingly intolerant of any dissent, Charles enjoyed dominating everyone around him. His family, his employees and even the locals – banned from using the traditional footpaths on his forested estate – have multiple reasons to bear a grudge. When Charles is killed in the woods, Inspector Simon Sturt finds conflicting motives and tangled relationships between Mrs Courtley, her daughter Pamela and the local men whose family had once owned the estate. But each has an alibi for the time of the murder and no one is talking…

£9.99

By D. Erskine Muir

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1941 by Methuen & Co Ltd, London

Paperback

189pp

ISBN 9781899000449

Available December 2021

Introduction by Curtis Evans

I Charles Shows His Temper

II Why They Married

III Who Was in the Yard?

IV Breakfast Party

V Scene with a Secretary

VI Last Appearance of Charles

VII The Shot in the Wood

VIII Police on the Scene

IX The Pellets

X The Handsome Agent

XI Finding Traces

XII Pamela and the Inspector

XIII A Tough Customer

XIV Fresh Discoveries at an Inn

XV Anne’s Strange Story

XVI What Was in the Letter?

XVII An Arrest

XVIII Trial and Error

XIX The Monument in the Wood

XX The Second Death

XXI Mrs. Gwyn’s Revelations

XXII Drugs

XXIII The Accident

XXIV At Bay

XXV The Third Death

XXVI The Last Struggle

Epilogue

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Charles was in a vile temper, and Anne was catching the full benefit of it. Anne was his wife, and she regretted that fact. She sat beside him in the great Rolls Royce, swirling towards their beautiful home, but even while they speeded along the country road she reflected bitterly that money did not outweigh a bad temper, inthe matrimonial scales.

She glanced at her husband, and her eyes travelled over his thin, rather distinguished face. She noted his cold, highly-intelligent grey eyes, his thick thatch of grey hair, and her gaze came to rest on the mouth which to her was now the key-note of his character. Large, thick-lipped, coarse and resolute. Perhaps that mouth ought alwaysto have warned her?

At that point his voice, with a disagreeable ring in it, broke across her reflections. “I am not going to discuss this any more, Anne. You can make up your mind to that. I’m too old to change my ways now. I don’t intend to start a flat in town. So say no more about it.”

“You’re very unreasonable,” she retorted, as coolly as her own rising indignation allowed. “I don’t suggest you should use the flat.

I know of course you’ve always hated such places. I simply ask you to let me have one. I know nothing would induce you to spend more of your time in town than you can help. But I don’t see why you should prevent my doing so.”

“Because I don’t choose to spend my money in that way, and I do what I like with my money.”

Anne would have liked to make no reply to that domineering remark, for she knew perfectly well she had better let the matter drop. But she was driven on by that incorrigible sense of having right on her side which prevents many a woman from tactfully holding her peace, and she rejoined, in a voice which even her own ears warned her was growing sharp: “Well, you needn’t take such an unreasonable line. You’re not fair to me, you never have been. You knew I always hated the country and I never expected to have to live in it…”

As her tones rose slightly Charles interrupted, more rudely than before. “We’ve had enough of that. Can’t you, for heaven’s sake, stop raking things up? I tell you I will not have you argue about it. I’ve decided—and I’m not going to change my mind. We’ve got Carron, and you’ll kindly be contented with that.”

The violence of his voice warned Anne not to reply and she turned away in order to prevent herself saying any more.

Silence fell between the two; angry, bitter silence. After a few minutes, Charles, who was now thoroughly roused, broke into speech again. “And while we’re on the subject of living down here, let me tell you I mean to put my foot down over Barclay. I will not have Pamela associating with that man.”

Anne looked away, pursing her lips together in her determination not to be drawn into further speech.

Charles went on, his tone growing nastier with each word he uttered. “She’s not of age yet, and I intend her to do what I wish. She’s not to see that man any more. I’ll not have him about the place, and that’s to be understood by all of you.”

“You’d better speak to her, then,” said Anne briefly.

“I certainly shall. And you’ll kindly not go behind my back and encourage her. This affair has got to end, and I’ll speak to her this evening!”

Anne made no reply at all, and after a furious glance at her, Charles flung himself back in his corner, slapping the pages of his evening paper angrily together, and muttering to himself.

They rushed on through the flat, luxuriant countryside, until the car turned off the high road. For a short interval they rolled along an utterly deserted by-road, with no houses, no farms, no inhabitants, until the big car turned in at a white gate and whirled down a short drive to the house. Charles instantly banged open the door on hisside, while the chauffeur was preparing to climb out of his seat, and dashed out and disappeared into the house. The chauffeur stolidly came round to open the door for his mistress.

The door of the house remained open, left so by Charles in his angry passage, but there was no sign or sound of life, merely the silence of a hot summer’s evening. The sun beat through the trees on to the grey stone front, the creepers hung still and straight in long trails around the windows, the bees hummed and roared softly in the mauve edgings of cat-mint that bordered the drive—beyond that all was stillness and somnolence.

For a moment Anne sat quite still. In her own way she was as furious as Charles in his. Returning to her home brought with it the familiar feeling of imprisonment, of resentment, of irritation deepening almost to hate. The mere aspect of the place, the knowledge that once across the threshold all her problems and difficulties would rise up and confront her, filled her with bitterness.

‘Rural peace’—that was the phrase which seemed to pass through her mind as she slowly collected her handbag and a few small parcels and stepped out of the car—‘Rural peace!’ How beautiful was the sound, and how bitterly she disliked the reality! Though (her sore, angry thoughts ran on) perhaps she hated the phrase because after all there was no true peace here—only ‘rural solitude’ and the jangling and jarring of personalities at strife.

She went into the house, crossed the hall, and went quickly upthe wide, bare, polished staircase to her own room, still absorbed in her thoughts. Perhaps it was the stillness and beauty of the hot, summery afternoon, perhaps the sudden feeling that had come over her as her eyes had taken in the outward aspect presented by the house, perhaps merely a heightened sense of the passing of time and life which the very season of early autumn seemed to bring to her each year now—but whatever the cause, she stood still in her room in a sudden passion of stormy feeling; revolt, anger, almost hatred.

She flung her hat and parcels down and walked across to the window. Mechanically she paused on her way and glanced at herself in the mirror, and a fresh access of bitterness welled up in her. She was nearly forty, and in one violent burst of feeling she realized that here was one potent source of unhappiness, for her life was passing, she must make the very most of the time that remained before middle age should be upon her. At present she emphatically did not feel herself ageing, she was burning with vitality, with desire to get the most out of life, and she was determined to snatch at any happiness which came her way before it was too late.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.