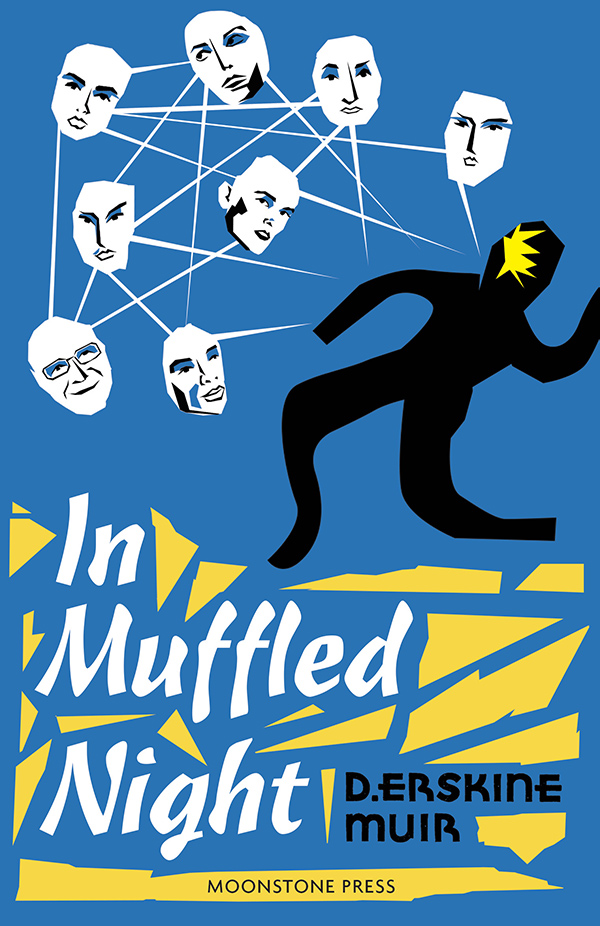

In Muffled Night

It was not at all a suitable house for a murder.

Helen Bailey is the live-in housekeeper to the wealthy Murray family. Tall, dark-haired and beautiful, the enigmatic Helen has long ensured that life at ‘The Towers’ ran smoothly for autocratic patriarch James Murray, his widowed son John, and grandchildren Alan and Glenda. When Helen is found dead in her blood-soaked bedroom, struck down in a horrific attack, the police must consider not only the family’s relationships but everyone close to them. Helen’s jewellery is missing, suggesting a robbery gone wrong, but the clues are confusing and contradictory. Dogged policework eventually points to one person, but have the authorities identified a cold-blooded murderer or an innocent person framed by others?

This classic detective novel is now back in print for the first time. Based on an unsolved real-life crime.

Dorothy Erskine Muir (1889-1977) was one of seventeen children (twelve who reached adulthood) of John Sheepshanks, Bishop of Norwich. She attended Oxford, worked as an academic tutor, and began writing professionally to supplement the family income after the unexpected death of her husband in 1932. Muir published historical biographies and local histories, as well as three accomplished detective novels, In Muffled Night (1933), Five to Five (1934) and In Memory of Charles (1941). Each is an intricate fictional account based on an unsolved true crime.

£9.99

By D. Erskine Muir

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1933 by Methuen & Co Ltd, London

Paperback

189pp

ISBN 9781899000401

Available August 2021

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

It was not at all a suitable house for a murder.

Of course there have been murders in the houses of the good and great. But “The Towers” seemed the embodiment of everything peaceful, sober, and respectable. It was a large house, on the Highstead Heights, above London, surrounded with big gardens, with glass-houses, a carriage-drive, a shrubbery, a small wood, and every appurtenance of the rich, solid, middle-class.

The mid-Victorians who built it, furnished it and lived in it, would always have felt that anything in the nature of a brutal blood-stained crime could not, in conformity with divine and natural law, be associated with such a house. Evenin the present day it had, owing to a series of rather peculiar circumstances, retained the atmosphere with which it had been impregnated by its first owners.

Still furnished in the style of the eighteen-eighties, the scheme of decoration seemed almost incredible to the modern young. A specimen of the modern girl might, and in fact did, feel extremely out of her element on entering this house. Diana Ford was of this species, and staying in the house for the first time, as a totally unprepared visitor, she came down to breakfast and entered the dining-room feeling akin to ‘stout Cortez when with eagle eyes he star’d’, and had she but had a companion they would have emulated that famous band and ‘looked at each other with a wild surmise’. As it was, she could only gaze round the room with a feeling of complete stupefaction.

Never had she seen such a room, or thought it possible that so complete a relic could remain unspoilt and untouched, and she stood looking about her and taking in its details with much amusement. She had read, in common with every one else, reconstructions of the mid-Victorian scene. She had even visited a model museum whose period-rooms included one with the setting of the eighteen-eighties.

Nothing, however, had forewarned her that she could one day actually sit down in a room still used for ordinary daily life and yet in itself an exact survival of those past days. It was rather a dark room. The heavy sash windows had their lower frames filled with squares of coloured glass. The buff blinds were neatly drawn down about a foot. Even such light as could enter through the restricted space thus left, had first to filter through deep cream lace curtains, hanging from the top of the high windows inbillowing folds to the floor. Completing this stout resistance against the sunlight were long thick curtains in a sort of rep material and of a deep-red tone, with vast red ropes catching in their swelling waists.

The carpet, also red, was very thick and soft, and stretched across the floor right up to the wainscot of the walls. Those walls were papered in the same slightly ominous shade of crimson. ‘Flock-paper’ thought Diana, with vague ideas of her readings floating through her mind, “that, I think, must be flock”. Large oil paintings, mostly landscapes, but including also scenes with fishing-boats, ducks on a pond, a village street, all heavily framed in gold, loomed from the walls. In one corner a fullsized statue of a woman in white marble leaned out into the room. In another a marble child lay asleep on a frilled marble cushion, ‘brought from Rome on a wedding trip’.

A sofa and two large arm-chairs and the heavy mahogany set of dining-room chairs were covered with what Diana mentally described as ‘carpet material’, by which term she meant a kind of velvet plush with a geometrical pattern in shades of drab, dark blue, and maroon. The mantelpiece was of heavy black marble, grained with white. At either end of it stood a tall Doric column in buff marble, copies of some pillars in a famous Grecian temple. In the middle stood alarge black marble clock, inlaid with malachite, and with the bronze figure of a draped woman sprawling across the top. Two Satsuma vases, one on either side of the clock, completed the array.

From the old-fashioned china bell-knob at the side dangled a placard, illuminated in heavy silver lettering, “Christ is the Head of this house, the Unseen Guest at every meal, the silent Listener to every conversation.”

“Well,” thought Diana, “I hope we all live up to that—though,after all,” she reflected, “I expect psycho-analysts think of our subconscious as a sort of listener to everything we say too.”

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.