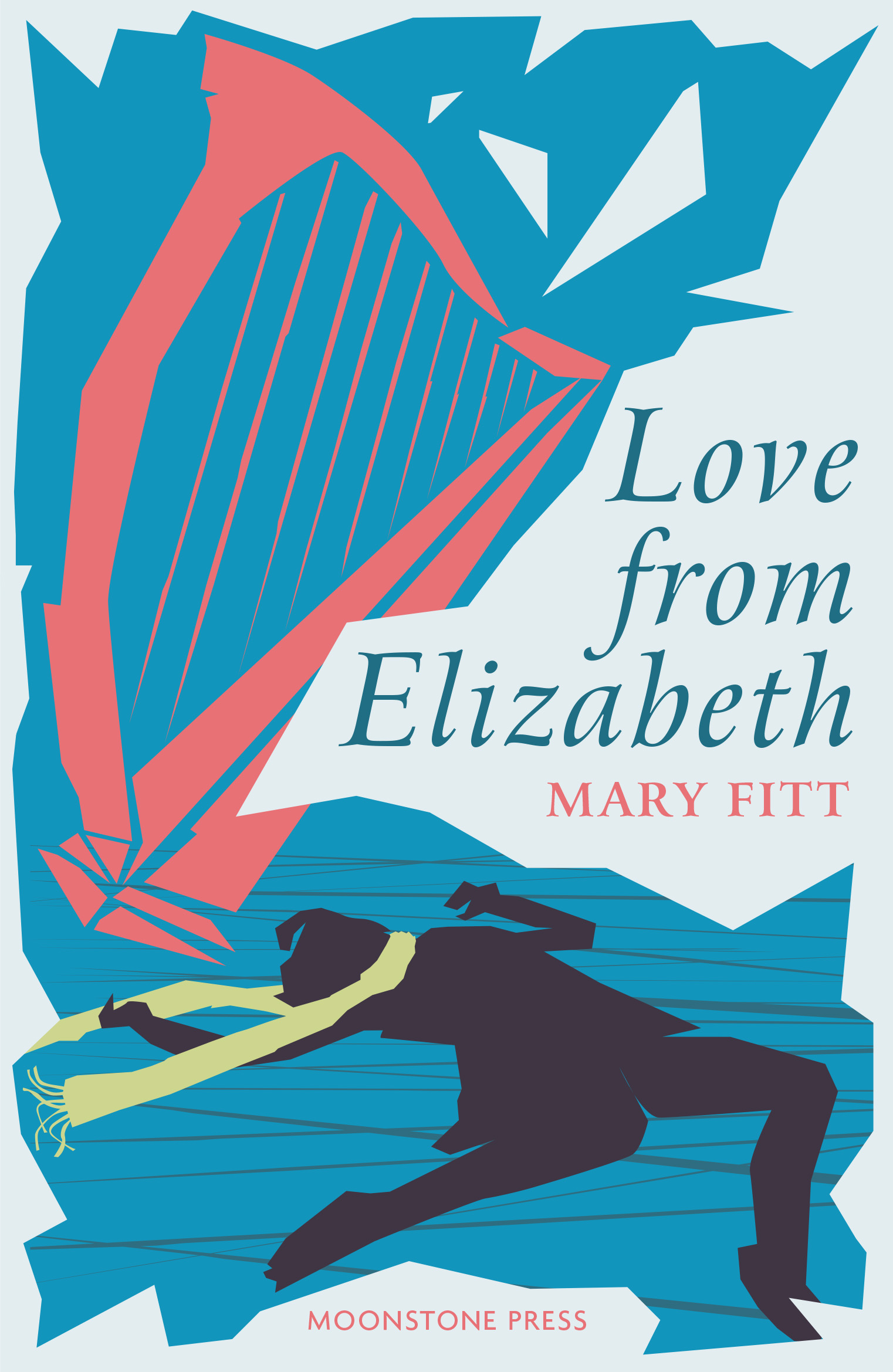

Love from Elizabeth

‘My great-aunt Liza is an old she-devil…..but she’s had a devilish raw deal.’

Lady Elizabeth Carn has ruled Tristowell Castle with an iron fist for 50 years. On the eve of her adored adopted daughter Augusta’s twenty-first birthday, far-flung family return to the castle, dredging up past resentments and conflicts. The next morning, Elizabeth is found strangled at her writing desk and nephew Palin Carn has disappeared in the night. Augusta, in love with Palin, cannot believe him capable of murder. The police disagree, but find more than one possible suspect with opportunity and motive. There is Veronica, Lady Elizabeth’s first adoptee, ostracized at age 18 for eloping with a local man, and returning to Tristowell for the first time with her teenage sons. Eccentric painter Jane Bossom, impulsively adopted at age 12 after the death of her parents but sent off 3 months later, has also returned to Tristowell to paint Augusta’s portrait. And there is fierce quiet Tenella, Elizabeth’s resident harpist, who clearly knows more than she is telling.

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1954 by Macdonald & Co, London

Paperback

252pp

ISBN 9781899000623

eISBN 9781899000630

Available July 2023

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Lady Elizabeth Carn sat at the head of the table in the dininghall of Tristowell Castle.

In the Minstrels’ Gallery Tenella Williams sat playing the harp. Tenella was Welsh, and so was her harp. She had brought it with her to Tristowell when she had come there over twenty years ago, and now its notes, as plaintive and incisive as ever, rang through the hall, refusing to form a background to the conversation below.

Lady Elizabeth rapped on the table. “Tenella, for heaven’s sake!” she called up angrily, “not Thomas Moore! You know I can’t bear him!”

Tenella swept her hands furiously over the harp-strings, but her small dark smile belied the action. She checked the quivering strings, and then glided into a soft Welsh melody.

Lady Elizabeth, after a nod of qualified approval, continued her conversation with the Bishop whom she had seated on her right. Neither he nor anyone else dared to ask her why she disliked the songs of Thomas Moore. Most of the diners knew, and all thought it best that the incident should be passed over as quickly as possible.

Tristowell Castle is a stone-built house at the head of a long inlet of the sea. It was built in Tudor times on the site of an earlier fortification, and it is completely Tudor in design and in tradition. Its façade consists of large mullioned windows on either side of a high porch led up to by a flight of stone steps. Above the porch is a balcony with an ornamental stone balustrade. The great doors open directly on to the dining-hall, which is stone-flagged; in Lady Elizabeth’s day the damp and the cold were not merely excluded but routed by the constantly-burning log fire in the enormous stone fireplace.

There was a fire burning even now, on this lovely evening in June, when the air was so soft and scented that some of the diners, the younger ones, would have liked the doors to have been left open, since it was not possible to get away… away.

“Your harpist plays beautifully, Lady Elizabeth,” said the Bishop. “What a charming idea—and what a charming name!”

He had been invited to dinner merely, having been recently appointed to a diocese in the south-west, and he knew nothing of his hostess except by a rather alarming hearsay.

Lady Elizabeth laughed. Her laugh, in her seventy-fourth year, was as melodious and as scornful as when she had been a débutante. “Which name, Bishop?” she said.

The Bishop said in surprise: “Was I mistaken? Didn’t I hear you call her ‘Tenella’?”

“Certainly,” said Lady Elizabeth. “But that’s not her name. Her name’s Mary Ann Williams, but of course I couldn’t have that.”

“Dear me!” said the Bishop, crumbling his bread. “And doesn’t she mind?”

“Why should she?”

“Well—perhaps people prefer to keep their own names, however inferior—and,” he added in an undertone, “their own personalities.”

Lady Elizabeth heard. “Nonsense!” she said. “People want above all things to escape from themselves—isn’t that so?”

She turned quickly to the fair, upright young man on her other side. She expected him to agree with her, because he would not have been sitting at her table at all if he had not been the son of one of her many cousins several times removed; for he was a doctor, and she retained an eighteenth century attitude towards medicine: she regarded its practitioners as little better than apothecaries or even barbers.

Ralph Ransome said coldly: “Perhaps—but they don’t like having their personalities forcibly removed.” His fair moustache failed to conceal a twitch of the lip that might or might not have been a smile.

Elizabeth gave him a hard stare, wondering if he were daring to contradict her. She decided that the remark was meant to be a witticism, something connected with surgery, on which no doubt his mind ran day and night. She disapproved of surgery, and often said with finality that she did not believe in The Knife; her tone suggested, as her great-nephew Palin had already remarked—though not to her—a carving-knife, and possibly also a carving-fork. Palin Carn sat at the other end of the table; he had been placed there by his great-aunt. She liked him, against her will and judgment, against her powerful determination. She also feared him; not for anything he could do to herself, but because he was attractive.

She intended to get rid of him. He had been here for one week, and that was too long. He was dark, good-looking and like all the Carns he had a sharp and irreverent tongue. She feared his tongue, for he was quicker-witted than she, and she would not be laughed at or even smiled at by anyone who sat at her table.

She had placed him at the foot of the table so that she could watch him. On his right hand she had set her elder sister, Lady Mary, and on his left hand the formidable Jane. Palin could hardly see Augusta from his position, and could not talk to her at all. Augusta, wedged between the Bishop and young Gerald, could neither talk to nor look at Palin.

Lady Elizabeth smiled.

She rightly judged that Palin, like all the Carns, was impressionable, and that he had fallen in love with her darling, her adopted daughter Augusta, whose twenty-first birthday, occurring in two days’ time, they were assembled to celebrate. Whether Augusta responded at all, Lady Elizabeth could not tell, though she watched closely.

But all the Carns were attractive, as Elizabeth knew to her cost, and this young man Palin, with his graceful ways, and his self-confidence acquired through residence in America, was the most dangerous Carn she had ever seen, excepting only her own particular Carn, that Percival who had charmed her and married her over fifty years ago, and then…

But this Carn was not going to get her darling, her Augusta.

She knew of a way to pour boiling oil on any such attack upon her citadel.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.