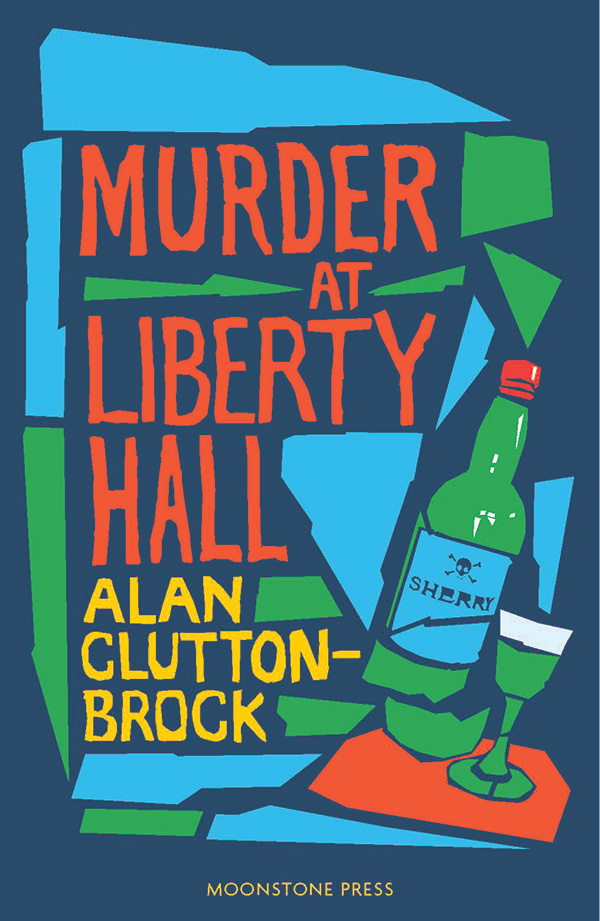

Murder at Liberty Hall (1941)

“You can’t expect a murderer to be able to have everything his own way “

Scientist James Hardwicke is invited to progressive co-educational Scrope House School to investigate a case of apparent pyromania among the student body. Although inclined to ignore this odd invitation, he is persuaded to accept by his friend Caroline, who wants a job at the school. It is May 1939, German refugees are streaming into England to escape the horrors of the Hitler regime, and the headmaster is worried about the ramifications of a refugee child being the culprit. Soon enough, James’ rather desultory investigation encompasses murder too, when sherry is poisoned at a faculty party. James must decide if there is a link between the fires and the murder, and whether the victim – the wife of the English teacher – was the intended victim or an accidental one.

Available: November 2020

£9.99

By Alan Clutton-Brock

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1941 by The Bodley Head, London

Paperback

238pp

ISBN 9781899000227

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

As we were leaving Edgeworth’s house and I was looking forward to my well-earned bed, Susan Dawes managed to get me alone outside the front door. ‘I should like to consult you, Mr. Hardwicke,’ she said, with the air of a conspirator.

‘What about?’ I asked, fearing that some more detection was to be asked of me.

‘I’d rather not tell you here,’ she answered. ‘It’s not about these fires, or at least only incidentally. Will you come to tea to-morrow? Our cottage is not very far from the Dower House.’

I had, of course, to accept her invitation, though I wondered whether I was going to be asked to solve all the problems of all the staff and be employed for ever in the school as a kind of universal aunt. I arrived punctually at the bleak cottage in which Mr. and Mrs. Dawes lived; it was at the top of a hill and exposed to all the winds.

‘We’re a long way from the school here,’ Mrs. Dawes said, ‘and that’s a great advantage, I can tell you. Richard and I can work here without any fear of being disturbed, and we aren’t expected to be always at the school.’

Was Richard, I wondered, meditating an erotic poem in some chilly study at the back of the house at this very moment?

‘Well now,’ began Mrs. Dawes, ‘I’ve a lot to tell you. I do think something ought to be done about it, and it had much better be by an outsider. Have you any influence with the Foreign Office?’

‘None whatever,’ I said.

Mrs. Dawes seemed to be disappointed. ‘But I expect you could do something,’ she said. ‘You must know people.’

‘Nobody at all,’ I said.

‘Oh, well,’ she said, ‘it’s really your advice I want. I’m pretty sure there’s a Nazi spy, either in the school or connected with it in some way. I can’t give you the source of my information, but I received a very serious warning. I know this sounds melodramatic but after all it’s the sort of thing that happens, isn’t it?’

‘I knew a man once,’ I said, ‘who couldn’t read any novels except those of Oppenheim. He said he was the only modern novelist who described the sort of thing that really happens.’

‘Exactly,’ said Mrs. Dawes.

‘But what makes you suspect a Nazi spy?’ I asked.

‘That’s what I can’t tell you,’ Mrs. Dawes said. ‘Oh, it’s not that I can’t trust you completely, but I don’t want to give other people away, and I was told in the strictest confidence. But I feel pretty sure, from one or two things I’ve heard, that some of the refugees on our staff have had threatening letters. I’ll give you an instance of the kind of thing that’s been happening. You know I work for a political monthly, the Popular Front, and I arranged for Rosenberg to contribute three consecutive articles. He sent in the first two and they were just what we wanted, a complete exposure of the weakness of the Axis and a reasoned appeal for an alliance with Russia. But he wouldn’t let me have the third, and wouldn’t give me a reason. He didn’t sign his name to the articles, of course, and we kept the secret of their authorship very carefully; in fact, we took what might be thought almost absurd precautions, though no doubt they were really very necessary. But one explanation of his failure to send the third article may be that he was threatened, and I shouldn’t be surprised if one of the refugees here—it might even be one of the older boys or girls—were being forced to send information abroad by threats about their relations who haven’t got away. And there’s one further point; supposing it’s a boy or girl who’s being forced to do the spying, you might expect him or her to find it a terrible strain. It would be an unspeakable position for a child at school, and the fires might be a symptom. I should think that’s just the kind of thing that would drive you to pyromania.’

‘I suppose it might,’ I answered.

‘And then there’s a further possibility,’ Mrs. Dawes continued. ‘Somebody might actually have been sent by the Nazis to pose as a refugee but really to work for them as a spy.’

‘Would it be worth their while,’ I asked, ‘to send someone here?’

‘You never can tell,’ said Mrs. Dawes. ‘This place is pretty well known. The difficulty is that I don’t know, and only an expert could know, how cunning spies really are. Would it, for example, be possible for a spy to appear as genuine as Rosenberg? Could he keep it up? Could he write articles which really were good anti-Nazi propaganda?’

‘That would seem to be going rather far,’ I said.

‘You think so?’ asked Mrs. Dawes. ‘Now that’s just the sort of thing I wanted to know.’

She had raised an interesting question, I thought, and I should certainly have liked to be in a position to let her know exactly how cunning spies can be.

‘Well,’ I said, ‘I’ll think about it, but we mustn’t be in too much of a hurry.’

‘Oh, no,’ she agreed, ‘and I’m quite content to put it into your hands.’

‘You’ve no other reason for suspecting Rosenberg except that he didn’t send in the third article?’ I asked.

‘No, not really,’ she replied, ‘and it’s only one of two possible explanations; he may have been threatened himself if he went on with the work. My information didn’t go beyond a general warning. Not as yet, that is…’

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.