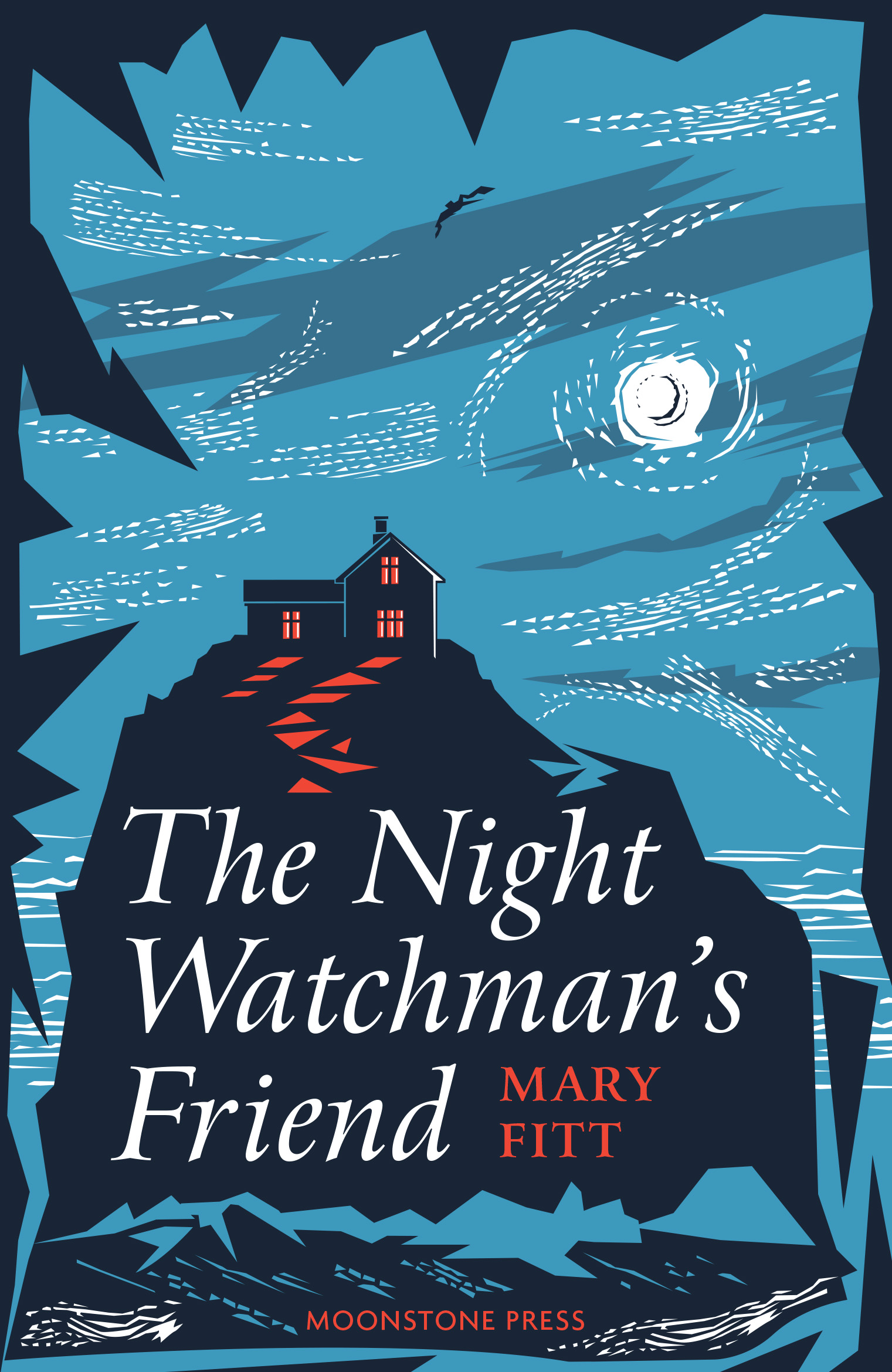

The Night-Watchmans Friend

“I shouldn’t have come back! They’ll never give up! There’s too much to lose!”

Night-watchman George Pollicott and reclusive Henry Rowles live a solitary and meagre existence in a hut along the towering Welsh sea wall. Twenty years earlier Pollicott had rescued the ailing Rowles, who now relied on the devoted Pollicott for all his needs. Suddenly Rowles writes a will bequeathing “all his personal estate” to his friend, but is found murdered that night. The police immediately set upon the night-watchman as the culprit, but the clues are confounding. Why was their hut ransacked? Who are the unrecognised signatories at the bottom of the will? What assets could the indolent Rowles possess that would motivate Pollicott to murder someone he clearly revered? And why, in his will, did Henry Rowles call himself John Henry Vincent Peter Dallingsworth Clairvaux, a man dead for forty years?

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1953 by Macdonald & Co, London

Paperback

238pp

ISBN 9781899000647

eISBN 9781899000654

Available October 2023

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

My name is Vaughan.

I am a retired solicitor. This was my status when the events I am about to relate temporarily recalled me from my retirement,

I trust for the last time.

Most men accept retirement as an unwelcome necessity. I chose mine. When the moment came I stepped happily from a busy practice in a small country town into the almost complete seclusion I had looked forward to for years—and I never regretted my choice, either of time or place or circumstance.

Fanciful people might say that I had been guided there by an all-seeing destiny, but personally I don’t think so. I don’t deny that it may have been so, but neither am I prepared to believe that our petty affairs are as important in the universal scheme as such a theory would imply. I happened to be present when these strange things occurred: that is all I know.

Yet I confess I am glad I was at hand to lend my small aid, and that it pleases me to think nobody else could have done so if I had not

chanced—assuming it was chance—to be there.

It all began one misty October evening when I was sitting by the fire reading by lamplight. The village where I live—St. Dyfrigin-Lostlands—is usually quiet. It lies in a very quiet part of the country, a low alluvial plain between the Bristol Channel and the hills, quite off the main route to the west; you would never think that it stretched between two large towns.

Even in the daytime you hear nothing but country sounds—farm machinery, the lowing of cows; perhaps a passing train in the distance; and if you walk along the Sea Wall you’ll certainly hear the bubbling of the curlew and the piping and trilling of the oyster catcher—a beautiful sound.

But this was evening, and it was absolutely quiet, except for the foghorn from down Channel, which one could scarcely hear indoors. It was so quiet that the tap on my window was as sharp and clear as if someone had thrown a pebble at it. My little dog barked, but I did not stir. I knew it was only my friend Lomax, the owner of Sluice Farm. He always announced himself this way. A moment later his rat-ta-tat sounded on the front door.

I heard the familiar exchanges as Mrs. Williams let Lomax in. Mrs. Williams is my housekeeper. She is a cheerful woman, fond of company herself, and convinced that anyone who spends as much time alone as I do is in need of being brightened up. Therefore she welcomed Lomax, who was my only regular visitor. I heard him say, as usual: “Now don’t you bother, Mrs. Williams. I’ll show myself in,” and her jolly voice replying, also as usual: “It’s no trouble at all, Mr. Lomax.” Then, triumphantly flinging open the door: “A visitor to see you, Mr. Vaughan!”

Lomax walked in, bringing something of the mist in with him. He wore no overcoat; drops of moisture clung to his thick tweed jacket and his fair hair and moustache. My little dog Mac greeted him effusively and stood up on his short hind legs to get attention.

“Hullo, Mac!” said Lomax absently and kindly, snapping his fingers at Mac, who staggered backward before him, still trying to imitate a circus dog.

“Come inside!” I said. “You announced yourself when you tapped on the window.” I closed my book: I was always glad to

see Lomax.

Mrs. Williams was wearing her hat and coat, but she couldn’t resist following Lomax into the room. “I’m glad you called, Mr. Lomax,” she said—and I knew what was coming—“it’ll cheer Mr. Vaughan up. It’s a nasty damp old night. Let me get you a cup of tea before you go. It won’t take a

minute.” Mrs. Williams is convinced that the only way to keep body and soul together in this very wet corner of the country is to drink frequent cups of tea.

“No, thanks,” said Lomax, “not for me.” He noticed her hat and coat and asked kindly: “Off to the concert, aren’t you? I’ve just dropped Mrs. Lomax there. The whole village seems to be going.”

“Mrs. Williams can make a good strong cup of tea,” I said perversely, knowing he’d prefer something even stronger, and thinking

also that the good woman looked disappointed.

Again Lomax said: “No, thanks, really.” He laughed: “I get enough good strong tea at home.”

Mrs. Williams exclaimed: “What? On your ration?” This was only three years after the war, when we could scarcely make our two ounces of tea last out the week. Some people had ways and means of getting round that, I believe. I myself would never allow such practices: I had strictly forbidden Mrs. Williams to exceed our ration, though I fancied sometimes she looked at me a little oddly when I spoke of the importance of keeping to the law in small things as well as great.

At this moment I was wishing she would go to her concert and not be inquisitive, when Lomax surprised me by saying in his slow, pleasant voice: “Well, to tell you the truth, I do get a bit extra now and then. Old Pollicott brings it along.”

“Oh yes, of course—he gets extra at his age,” said Mrs. Williams, nodding and smiling. “Well then, I’ll say good night, Mr. Lomax.”

She added, turning to me: “I’ll be back about half-past ten, sir.”

I said, “It’s quite all right,” glad to hear the last of the conversation about tea, and quite unaware that it, too, had its significance among the events of that fatal evening.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.