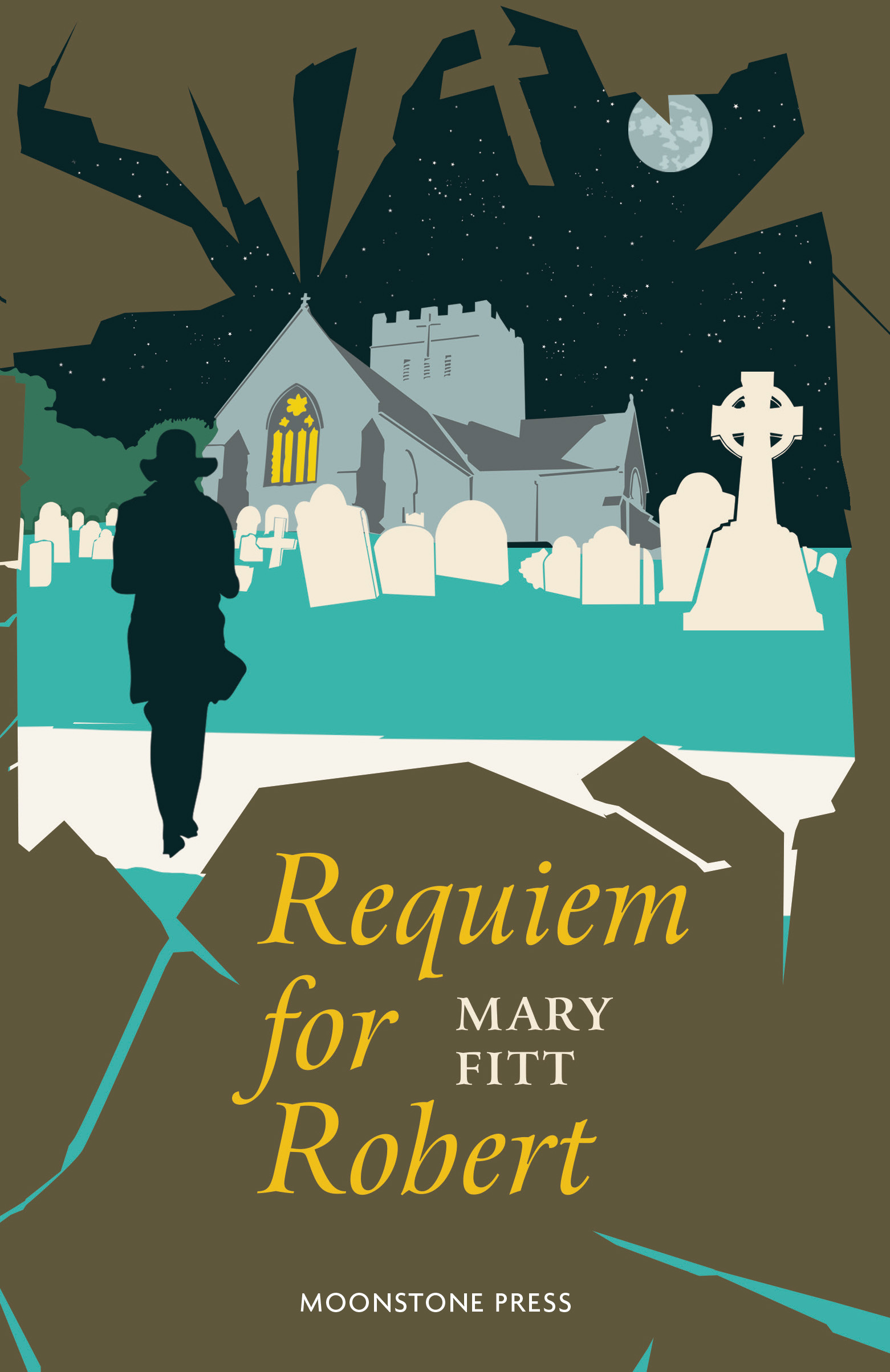

Requiem for Robert

‘When a man has three separate notices by three different women inserted in the local paper, and he’s my own namesake besides, I feel I owe him something.’

Sequential death notices appear for Robert Raynald: one by his mother, one by his estranged wife, one by his daughter. This odd approach draws the attention of Superintendent Mallett and his friend Dr. Fitzbrown. The inquest had decided that Raynald shot himself whilst temporarily insane, but his daughter Geraldine is not convinced and presents enough evidence to arouse the investigator within Mallett. Raynald’s story is presented in flashbacks, as Mallett and Fitzbrown build a picture of his life through the people who knew him best. Requiem for Robert combines the excitement of a detective story with a haunting reading of character.

£9.99

By Mary Fitt (pseudonym of Kathleen Freeman)

Introduction by Curtis Evans, vintage crime historian

First published in 1942 by Michael Joseph Ltd

Paperback

284pp

ISBN 9781899000524

eISBN 9781899000531

Available Sept 2022

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

Superintendent Mallett watched the hotel guests as one by one they rose and left the breakfast-room, in the same order as they had entered it: first a tall old lady with a forward stoop and a black-ribboned pince-nez which she placed on her nose just as she reached the door; then a stout middle-aged lady who leaned on a stick, and whose hands sparkled with rings; and soon after her a broad-shouldered yet nervous-looking grey-haired man who had been sitting just behind her, and to whom she had flung an occasional word across her shoulder during the meal. Mallett had noticed that the two ladies had ignored each other.

Mallett’s observation of the hotel guests was automatic and casual. He was staying here for a few days only, on other business; and with him was his friend Dr Fitzbrown. It was almost a holiday; yet he wondered what he was going to do with himself between the meetings which had brought him here. The place was beautiful, among the mountains, with a rushing trout-stream outside; but the time was mid-winter, and this morning the mist lay thick and cold in the valley, so that driving was unattractive, and walking, even if one liked walking, mere exercise. Mallett hummed to himself the lines of a favourite song:

Yes, I hate walking; I am not, I fear,

In harmony with Nature here.

The motion, a monotonous criss-cross,

Exasperating loss

Of energy, becomes grotesque

With constant repetition, like a name

Familiar, and my whole frame,

Extremities and entrails, feels

Resentful numbness, at each jar of heels.

Fitzbrown looked up from his paper. ‘What did you say?’ ‘Oh, nothing,’ said Mallett hastily, drumming with his fingers on the table. It was one of his minor chagrins that whenever he hummed a tune or murmured the words of a song, his companion always mistook it for conversation. He added, after a moment,‘I was wondering what you intended to do this morning.’ He glanced towards the long windows, but the curtains were not yet drawn. ‘Neither the town nor the country seems to offer any brightprospects, and I don’t care much for the idea of sitting all morning in the lounge with those other people.’ He sighed. ‘One loses the art of taking holidays.’

‘Oh, nonsense,’ said Fitzbrown impatiently. He bolted his last piece of toast and marmalade, looked at his wrist-watch, and glanced round him as if expecting the first patient to enter. ‘There’s always something to do if you look about you. I know perfectly well what I’m going to do this morning. You can please yourself, of course.’

‘If it doesn’t involve too much walking—’ said Mallett.

Fitzbrown rose. ‘About half an hour,’ he said, ‘uphill. We shall have to start in ten minutes. We could take the car, but I prefer to walk.’ He ran a severe eye over Mallett’s bulky form. ‘A walk would do you good, too.’

He turned away. Mallett called him back. ‘Here, I say! You haven’t said where we’re going.’

‘I am going,’ said Fitzbrown, ‘to a Requiem Mass – for Robert.’

‘Robert!’ said Mallett. ‘Who’s Robert?’

Fitzbrown came back to the table. ‘I don’t know,’ he said; ‘but when a man has three separate notices, by three different women, inserted in the local paper, and he’s my own namesake besides, I feel I owe him something. Also I’d like to see how they do these things.’ Mallett picked up that paper and ran his eye down the left-hand column:

Raynald. On December 14th, at High Cross Hall, suddenly, Robert, devoted son of Sarah Raynald, in his forty-sixth year. Requiem Mass at the Church of St Primus and St Felician, 10 a.m., Friday, December 18th. R.I.P.

Raynald. On December 14th, at High Cross Hall, Robert, dearly-loved husband of Natalie. Requiem Mass at the Church of St Primus and St Felician, 10 a.m., Friday, December 18th.

Raynald. On December 14th, at High Cross Hall, Robert, beloved father of Geraldine Raynald. Requiem Mass at the Church of St Primus and St Felician, 10 a.m., Friday,December 18th. R.I.P.

‘H’m,’ said Mallett. ‘They look alike, but there are differences. It seems as if there were some rivalry between these good ladies – some slight struggle for possession of the deceased Robert. I wonder what “suddenly” implies. It’s odd in a man of forty-five.’

‘To me,’ said Fitzbrown, ‘it suggests suicide, at the very least.’ Mallett nodded. ‘Quite so.’ He got up and pushed the folded newspaper into his pocket. ‘I’ll come with you.’

‘Meet me in the vestibule in five minutes,’ said Fitzbrown.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.