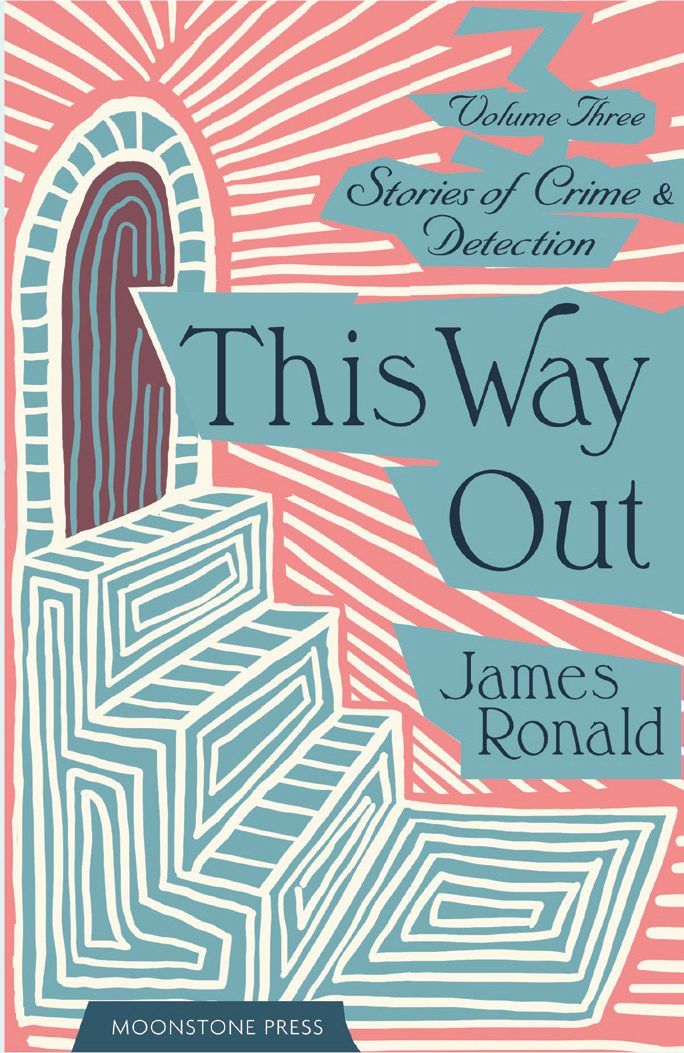

This Way Out

‘The perfect murder must be so simple that no one would suspect it to be murder.’

Volume Three contains a novel, a novelette and a short story:

This Way Out Philip Marshall is locked in a long and hellish marriage with his wife Cora, with divorce not an option. Cora delights in tormenting Philip, ready to pour bile in his ear at the slightest provocation; complaining of “his weaknesses…his failure as a money-maker…his deficiencies as a lover” to almost anyone who will listen. Home life is so unpleasant that their son John has moved out, telling his landlady he is an orphan. By chance, Philip meets young Mary Grey and finds the warmth and tenderness his life has missed. Longing for escape and a chance at redemption, Philip begins planning the perfect murder, but things do not go to plan… This Way Out was the basis of the Charles Laughton movie The Suspect (1944).

Diamonds of Death A humorous ‘pulp fiction’ story that involves a stolen diamond necklace, American gangsters, murder and romance.

Ruined by Water What happens when you mix a crooked bank clerk and a new reservoir?

JAMES JACK RONALD (1905-1972) was a prolific writer of pulp fiction, mystery stories and dramatic novels. Raised in Glasgow, Ronald moved to Chicago aged 17 to ‘earn his fortune’, later returning to the UK to pursue a writing career. His early works were serializations and short stories syndicated in newspapers and magazines around the world. Ronald wrote under a number of pseudonyms, including Michael Crombie, Kirk Wales, Peter Gale, Mark Ellison and Kenneth Streeter among others. Several books were adapted into films, including Murder in the Family (1938), The Witness Vanishes (1939), and The Suspect (1944).

£10.99

Out of stock

By James Ronald

Introduction by Chris Verner

First published in 1930s by Rich and Cowan and others.

Paperback

290pp

ISBN 9781899000708

eISBN 9781899000715

Available February 2024

Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review.

They were telling stories at the other end of the bar and Philip wanted to join them but Simmons had a firm grip of his sleeve. Simmons was talking volubly, the words tripping over his tongue and breaking off their final letters. He was telling Philip about a book he intended to write and gradually leading up to asking for the loan of a pound. For years he had been telling people about this book as often as he could grip a sleeve and edge the wearer into a corner. As a prelude to borrowing money it had worked fairly well at first—for it seemed stingy to refuse a small loan to a man about to make a fortune out of serial, film, and book rights—but now few habitués of ‘The Hole in the Wall’ would listen to him.

Before he was thirty Simmons had written three novels of promise but now he was thirty-five and for years had not written a line. He still described himself as a novelist and was hurt if anyone suggested he should look for a job. At seven every evening he swaggered into the saloon bar of ‘The Hole in the Wall’ with a shilling or so in his pocket and after closing time he wavered out again with a skinful of beer and most of his shilling. He never paid for more than his first drink of the evening; the rest grudgingly was supplied by habitués of the pub. Frequently the regulars vowed to leave him out when they ordered a round but when they came to pay, invariably they found that Simmons’s pint of bitter had included itself in the order.

For the third time the barman said wearily: “Time, gentlemen, please.”

“Two pints of bitter,” said Simmons, pushing an empty tankard across the bar. As a matter of form, he went through the motions of fumbling for money before he said to Philip: “You’ll have to pay, old boy. I’m broke.”

“Sorry, sir. It’s after time.”

“But I ordered them five minutes ago. You heard me, didn’t you, Marshall, old boy?”

“No,” said Philip.

The barman moved on. “Come along, gentlemen. Drink up, please. It’s after time.”

Simmons hammered with his tankard on the bar. “How the hell can I drink up when I haven’t anything to drink?”

“Let’s go,” said Philip, taking his arm. “It’s late.”

“Damned if I do,” retorted Simmons, hammering louder than before. “I ordered drinks ten—fifteen minutes ago and I’m going to stand here till I get them if I have to stand here all night.”

The landlord, a phlegmatic man with immense shoulders, came out of his den behind the bar and stood looking at Simmons. The sprinkling of customers who were finishing drinks craned their necks, hoping to see Simmons bodily thrown out. The landlord was capable of doing it. An ex-prize-fighter, he was built like a champion, but he had not gone far in the ring because he had a weak stomach. He liked to talk about his stomach, and he liked Philip Marshall because Philip was the only one of his regular customers who showed any interest in it. He was equal to handling twelve of Simmons, weak stomach or no weak stomach.

In silence, the regulars waited for something to happen. But nothing happened. Nothing, at least, worth watching. For a moment the landlord stared at Simmons and then looked down in mild surprise at the hammering tankard. Simmons stopped pounding the bar. He put down the tankard. The landlord raised a flap in the counter and followed his departing customers to the door. “Good night, gentlemen. See you tomorrow.”

And the devil of it was, reflected Philip, he probably would. He would see them all tomorrow, Philip included. At the age of forty-six, Philip had become a pub-haunter, a regular, one of the coterie that nightly trooped out of the ‘Hole in the Wall’ a few minutes after closing time. Most of the others had the same reason as he for lingering as long as possible in the place; it was so much pleasanter than home.

Fresh air struck Simmons like a physical blow and sent him reeling diagonally against the wall. Philip followed without haste and took his arm.

“I’m going to be sick.”

“You’ll be all right in a moment.”

“I tell you; I’m going to be sick. I ought to know.” Simmons was right. In wracking spasms, he rid himself of all he had consumed, and then Philip guided him home through slumbering streets.

Simmons ran on garrulously about his book. It was going to be a mystery novel but ordinary thrillers could no more be compared to it than a pimple can be compared to Mount Everest. The trouble with most mystery novels, he said, was that they were too involved. The murders were done with revolvers hidden in clocks or fountain pens or radios. That was all rot. The perfect murder must be so simple that no one would suspect it to be murder.

An arranged accident was the perfect murder.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.